Sarcoma (bone and soft tissue sarcoma)

This optimal cancer care pathway is intended to guide the delivery of consistent, safe, high-quality and evidence-based care for people with sarcoma.

The pathway aligns with key service improvement priorities, including providing access to coordinated multidisciplinary care and supportive care and reducing unwanted variation in practice.

The optimal cancer care pathway can be used by health services and professionals as a tool to identify gaps in current cancer services and to inform quality improvement initiatives across all aspects of the care pathway. The pathway can also be used by clinicians as an information resource and tool to promote discussion and collaboration between health professionals and people affected by cancer.

The following key principles of care underpin the optimal cancer care pathway.

Patient-centred care

Patient- or consumer-centred care is healthcare that is respectful of, and responsive to, the preferences, needs and values of patients and consumers. Patient- or consumer-centred care is increasingly being recognised as a dimension of high-quality healthcare in its own right, and there is strong evidence that a patient-centred focus can lead to improvements in healthcare quality and outcomes by increasing safety and cost-effectiveness as well as patient, family and staff satisfaction (ACSQHC 2013).

Safe and quality care

This is provided by appropriately trained and credentialled clinicians, hospitals and clinics that have the equipment and staffing capacity to support safe and high-quality care. It incorporates collecting and evaluating treatment and outcome data to improve the patient experience of care as well as mechanisms for ongoing service evaluation and development to ensure practice remains current and informed by evidence. Services should routinely be collecting relevant minimum datasets to support benchmarking, quality care and service improvement.

Multidisciplinary care

This is an integrated team approach to healthcare in which medical and allied health professionals consider all relevant treatment options and collaboratively develop an individual treatment and care plan for each patient. There is increasing evidence that multidisciplinary care improves patient outcomes.

The benefits of adopting a multidisciplinary approach include:

- improving patient care through developing an agreed treatment plan

- providing best practice through adopting evidence-based guidelines

- improving patient satisfaction with treatment

- improving the mental wellbeing of patients

- improving access to possible clinical trials of new therapies

- increasing the timeliness of appropriate consultations and surgery and a shorter timeframe from diagnosis to treatment

- increasing the access to timely supportive and palliative care

- streamlining pathways

- reducing duplication of services (Department of Health 2007b).

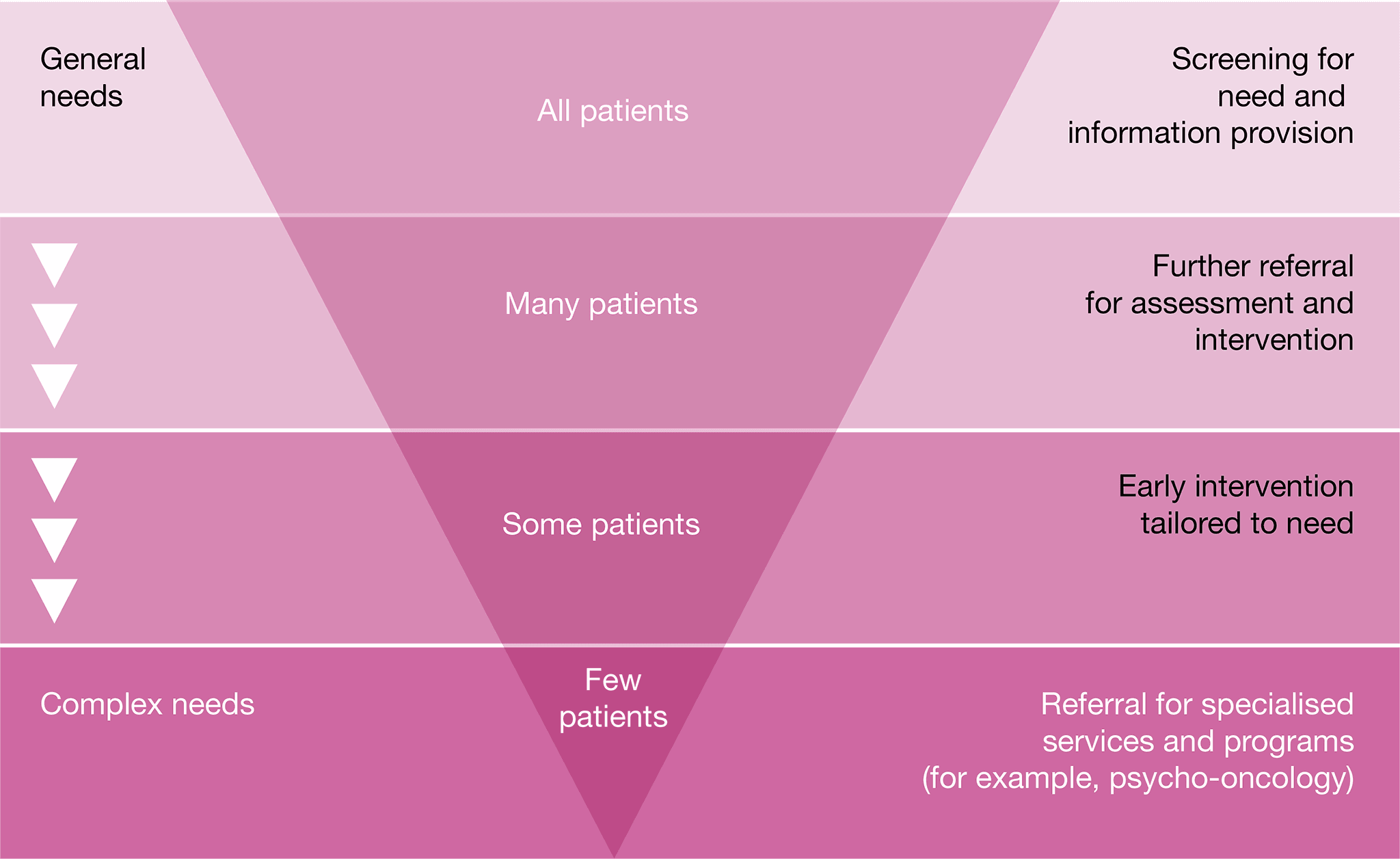

Supportive care

Supportive care is an umbrella term used to refer to services, both generalist and specialist, that may be required by those affected by cancer. Supportive care addresses a wide range of needs across the continuum of care and is increasingly seen as a core component of evidence-based clinical care. Palliative care can be part of supportive care processes. Supportive care in cancer refers to the following five domains:

- physical needs

- psychological needs

- social needs

- information needs

- spiritual needs.

All members of the multidisciplinary team have a role in providing supportive care. In addition, support from family, friends, support groups, volunteers and other community-based organisations make an important contribution to supportive care.

An important step in providing supportive care is to identify, by routine and systematic screening (using a validated screening tool) of the patient and family, views on issues they require help with for optimal health and quality-of-life outcomes. This should occur at key points along the care pathway, particularly at times of increased vulnerability including:

- initial presentation or diagnosis (the first three months)

- the beginning of treatment or a new phase of treatment

- change in treatment

- change in prognosis

- end of treatment

- survivorship

- recurrence

- change in or development of new symptoms

- palliative care

- end-of-life care.

Following each assessment, potential interventions need to be discussed with the patient and carer and a mutually agreed approach to multidisciplinary care and supportive care formulated (NICE 2004).

Common indicators in patients with sarcoma that may require referral for support include:

- pain

- fatigue

- mobility issues such as limb weakness

- difficulty sleeping

- distress, depression or fear

- poor performance status

- living alone or in remote areas, or being socially isolated

- having caring responsibilities for others

- cumulative stressful life events

- existing mental health issues

- financial stress

- work- or study-related stress

- Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status

- being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background.

Depending on the needs of the patient, referral to an appropriate health professional(s) and/or organisation(s) should be considered including:

- an adolescent and young adult (AYA) representative

- community-based support services (such as Cancer Council Australia)

- a dietitian

- an exercise physiologist

- a genetic counsellor

- a fertility expert

- a nurse practitioner and/or specialist nurse

- an occupational therapist

- peer support groups (contact the Cancer Council on 13 11 20 for more information)

- a physiotherapist

- a psychologist or psychiatrist

- a social worker

- specialist palliative care

- a speech therapist.

See the Appendix for more information on supportive care and the specific needs of people with sarcoma.

Care coordination

Care coordination is a comprehensive approach to achieving continuity of care for patients. This approach seeks to ensure that care is delivered in a logical, connected and timely manner so the medical and personal needs of the patient are met.

In the context of cancer, care coordination encompasses multiple aspects of care delivery including multidisciplinary team meetings, supportive care screening/assessment, referral practices, data collection, developing common protocols, providing information and individual clinical treatment.

Improving care coordination is the responsibility of all health professionals involved in patient care and should therefore be considered in their practice. Enhancing continuity of care across the health sector requires a whole-of-system response – that is, that initiatives to address continuity of care occur at the health system, service, team and individual levels (Department of Health 2007c).

Communication

The healthcare system and all people within its employ are responsible for ensuring the communication needs of patients, their families and carers are met. Every person with cancer will have different communication needs, including cultural and language differences. Communication with patients should be:

- timely

- individualised

- truthful and transparent

- consistent

- in plain language (avoiding complex medical terms and jargon)

- culturally appropriate

- active, interactive and proactive

- ongoing

- delivered in an appropriate setting and context

- inclusive of patients and their families (with the patient’s consent).

In communicating with patients, healthcare providers should:

- listen to patients and act on the information provided by them

- encourage expression of individual concerns, needs and emotional states

- tailor information to meet the needs of the patient, their carer and family

- use professionally trained interpreters when communicating with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- ensure the patient and/or their carer and family have the opportunity to ask questions

- ensure the patient is not the conduit of information between areas of care (it is the provider’s and healthcare system’s responsibility to transfer information between areas of care)

- take responsibility for communication with the patient

- respond to questions in a way the patient understands

- enable all communication to be two-way.

Healthcare providers should also consider offering the patient a Question Prompt List (QPL) before their consultation, plus recordings or written summaries of their consultations. QPLs are effective in improving the communication, psychological and cognitive outcomes of cancer patients (Brandes et al. 2014). Providing recordings or summaries of key consultations may improve the patient’s recall of information and patient satisfaction (Pitkethly et al. 2008).

Research and clinical trials

Where practical, patients should be offered the opportunity to participate in research and/or clinical trials at any stage of the care pathway. Research and clinical trials play an important role in establishing efficacy and safety for a range of treatment interventions, as well as establishing the role of psychological, supportive and palliative care interventions (Sjoquist & Zalcberg 2013).

While individual patients may or may not receive a personal benefit from the intervention, there is evidence that outcomes for participants in research and clinical trials are generally improved, perhaps due to the rigour of the process required by the trial. Leading cancer agencies often recommend participating in research and clinical trials as an important part of patient care. Even in the absence of measurable benefits to patients, participating in research and clinical trials will contribute to the care of cancer patients in the future (Peppercorn et al. 2004).

Timeframes should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce patient distress. The following recommended timeframes are based on consensus expert advice from the Sarcoma Working Group.

Timeframes for care

| Step in pathway | Care point | Timeframe |

| Presentation, initial investigations and referral | 2.3 Referral to specialist | A suspected sarcoma should be referred to a specialist within two weeks; first specialist assessment within four weeks of referral. |

| Diagnosis, staging and treatment planning | 3.1 Diagnostic work-up | Completion of all investigations within two

weeks of first specialist assessment. |

| 3.2.4 Multidisciplinary team

meeting |

All newly diagnosed patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting before beginning treatment. | |

| Treatment | 4.2 Treatment options | Patients begin their treatment within three

weeks of the decision to treat. |

The optimal cancer care pathway outlines seven critical steps in the patient journey. While the seven steps appear in a linear model, in practice, patient care does not always occur in this way but depends on the particular situation (such as the type of cancer, when and how the cancer is diagnosed, prognosis, management, patient decisions and the patient’s physiological response to treatment).

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies and include many anatomical sites and subtypes. Sarcomas account for less than 1 per cent of all adult solid malignant cancers, and given the number of histologic types, any given type of sarcoma is extremely rare (Herzog 2005). The pathway includes all bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST), Kaposi’s sarcoma and desmoid fibromatosis are excluded. This document refers to ‘sarcoma’ when the recommendations are intended to apply to both bone and soft tissue sarcomas.

Special considerations

The pathway describes the optimal cancer care that should be provided at each step. Sarcomas disproportionately affect AYA patients, with more than half of all cases being diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39 (Davis et al. 2017). The significant developmental change that occurs during this life stage complicates a sarcoma diagnosis, often leading to unique physical, social and emotional impacts at the time of diagnosis and throughout the treatment pathway (Smith et al. 2012). Ensuring access to expert AYA health professionals who understand the specific needs of this population, and ensuring they are linked with a youth cancer service, are essential considerations in providing care to this group. Further considerations for this group are outlined under [ocp-link to=special-groups]Populations with special needs.

This step outlines recommendations for the prevention and early detection of sarcoma. Eating a healthy diet, avoiding or limiting alcohol intake, regular exercise and maintaining a healthy body weight may help reduce cancer risk.

The causes of sarcoma are not fully understood, and there is currently no clear prevention strategy.

Risk factors for bone sarcoma may include:

- family history (slight increased risk)

- history of retinoblastoma

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- history of childhood cancer

- prior abnormalities such as Paget’s disease, avascular necrosis or polyostotic fibrous dysplasia

- past treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy

- exposure to certain chemicals (for example, vinyl chloride and dioxin)

- age: adolescent/young adult (less than 30) or over 50 years.

Risk factors for soft tissue sarcoma include:

- familial syndromes

- history of cancer

- past treatment with radiation therapy

- prolonged lymphoedema

- exposure to certain chemicals (for example, vinyl chloride and dioxin)

- age (over 50 years).

There is no population-based screening program for sarcoma. There is no evidence of benefit of population-based screening, including genetic screening.

This step outlines the process for establishing a diagnosis and appropriate referral. The types of investigation undertaken by the general or primary practitioner depend on many factors, including access to diagnostic tests and medical specialists and patient preferences.

The following signs and symptoms may indicate sarcoma. Symptoms of bone sarcoma include:

- persistent non-mechanical pain in any bone lasting more than a few weeks

- referred pain

- pain that is unremitting and unresponsive to analgesics

- nocturnal bone pain

- a mass

- swelling

- a limp

- limited mobility or loss of limb function

- fractures with minimal trauma.

Symptoms of soft tissue sarcoma include:

- persistent pain

- any deep mass

- any superficial mass with a diameter exceeding 5 cm

- a small but growing mass

- a rapidly growing change in a mass (over months)

- a mass with atypical physical characteristics – for example, hardness, firmness, irregularity and/or atypical location

- a mass where there is no associated history of trauma (differential diagnosis, for example, haematoma).

Examinations/investigations should include:

- medical history and baseline blood tests

- physical examination including assessing the physical characteristics of the mass and assessing the regional lymph nodes

- plain x-ray (if there is bone pain)

- specialist referral for a soft tissue lump (ultrasound is often of limited use and may be misleading).

The decision to perform a biopsy should be determined by a specialist in musculoskeletal tumours who is part of a specialist sarcoma multidisciplinary team.

All patients with suspected sarcoma should be referred to a specialist sarcoma multidisciplinary team before biopsy (Cancer Council Australia Sarcoma Guidelines Working Party 2014, ESMO 2014a, ESMO 2014b).

Patients aged under than 16 years should attend a paediatric specialist treatment centre. Patients aged 16–18 years should attend either a paediatric or adult specialist centre with access to a multidisciplinary team and supportive services appropriate to the AYA age group.

Referral for suspected sarcoma should incorporate appropriate documentation sent with the patient including:

- a letter that includes important psychosocial and medical history, family history, current symptoms, medications and allergies

- results of current clinical investigations (imaging reports)

- results of all prior relevant investigations

- any prior imaging, particularly a hard copy or CD where online access is not available (lack of a hard copy should not delay referral)

- notification if an interpreter service is required.

Timeframe for referral to a specialist

Timeframes for referral to a specialist should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce patient distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Sarcoma Working Group1:

- A suspected sarcoma should be referred to a specialist within two weeks.

- The first specialist assessment should occur within four weeks of referral.

The supportive and liaison role of the GP and practice team in this process is critical.

An individualised clinical assessment is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family; referral should be as required.

In addition to common issues identified in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include:

- treatment for physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue, musculoskeletal dysfunction, reduced oral intake and issues with activities of daily living

- help with the emotional distress of dealing with a potential cancer diagnosis, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems, stress and adjustment difficulties

- guidance for financial, education and/or employment issues (such as loss of income and having to deal with travel, and accommodation requirements for rural patients and caring arrangements for other family members)

- appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- allied health evaluations as appropriate.

Effective communication is essential at every step of the care pathway. Effective communication with the patient and carer is particularly important given the prevalence of low health literacy in Australia (estimated at 60 per cent of Australian adults) (ACSQHC 2013).

The general or primary practitioner should:

- provide the patient with information that clearly describes who they are being referred to, the reason for referral and the expected timeframe for appointments

- support the patient while waiting for the specialist appointment.

Step 3 outlines the process for confirming the diagnosis and planning subsequent treatment. The guiding principle is that interaction between appropriate multidisciplinary team members should determine the treatment plan.

Diagnostic work-up should include:

- history and examination

- staging: local – MRI, thallium or PET scans; systemic – bone scan, PET/CT, CT chest

- image-guided biopsy – percutaneous needle or open

- examination of tumour tissue by histological, immuno-histochemical, molecular pathological and cytogenetic methods, as appropriate

- lymph node biopsy (if functional imaging is positive or clinical examination suspicious).

The tumour should be staged on completion of investigations.

To confirm malignancy, and provide a histological diagnosis, biopsy should be performed after all imaging modalities have been completed and reviewed by the specialist. Image-guided needle core biopsy (NCB) is the preferred method, performed by a radiologist who is familiar with the issues of sarcoma biopsy in a specialist sarcoma unit setting with appropriate multidisciplinary input.

The histological diagnosis and determination of grade and subtype of sarcomas should be undertaken by an appropriately trained histopathologist. Histological diagnosis should be made according to the 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) classification (ESMO 2014b).

Timeframe for diagnosis

Timeframes should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce patient distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Sarcoma Working Group:2

- Complete all investigations within two weeks of first specialist assessment.

The responsibilities of the multidisciplinary team are to:

- nominate a team member to coordinate patient care and identify this person to the patient

- nominate a team member to be the lead clinician (the lead clinician may change over time depending on the stage of the care pathway and where care is being provided) and identify this person to the patient (if different from the care coordinator)

- develop and document an agreed treatment plan at the multidisciplinary team meeting (including consideration of clinical trial options)

- communicate/circulate the agreed multidisciplinary team treatment plan to relevant team members, including the patient’s general practitioner

- inform quality and safety improvements, collect data and benchmark outcomes.

The general or primary medical practitioner who made the referral is responsible for the patient until care is passed to another practitioner.

The general or primary medical practitioner may play a number of roles in all stages of the cancer pathway including diagnosis, referral, treatment and coordination and continuity of care as well as providing information and support to the patient and their family.

The care coordinator is responsible for ensuring there is continuity throughout the care process and coordination of all necessary care for a particular phase. The care coordinator may change over the course of the pathway.

The lead clinician is responsible for overseeing the activity of the team.

The multidisciplinary team should comprise the core disciplines that are integral to providing good care. Team membership will vary according to cancer type but should reflect both clinical and psychosocial aspects of care. Additional expertise or specialist services may be required for some patients (Department of Health 2007b).

Team members may include:

- a cancer nurse (with appropriate expertise)*

- a care coordinator (as determined by multidisciplinary team members)*

- a dietitian*

- a medical oncologist*

- a musculoskeletal radiologist*

- a paediatric surgeon*

- a pathologist*

- a radiation oncologist*

- a reconstructive surgeon*

- a social worker*

- a surgical oncologist*

- an expert in providing culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (this may be an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health worker, health practitioner or hospitality liaison officer)*

- an expert in the psychosocial care of AYA (with preference for a representative from a youth cancer service)*

- an orthopaedic oncologist*

- an orthotist/prosthetist*

- a clinical trials coordinator

- a fertility specialist

- a general practitioner

- a nuclear medicine specialist

- a palliative care specialist

- a pharmacist

- a physiotherapist and/or exercise physiologist

- a psychiatrist

- a psychologist

- a rehabilitation physician

- a speech therapist

- a thoracic surgeon.

- an occupational therapist

* Core members of the multidisciplinary team are expected to attend most multidisciplinary team meetings either in person or remotely.

All newly diagnosed patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting before beginning treatment. The level of discussion may vary depending on clinical and psychosocial factors. Teams may agree standard treatment protocols for non-complex care facilitating patient ascertainment and associated data capture.

A treatment plan for each case should be discussed at the beginning of treatment to determine timing and the choice of surgical resection, surgical reconstruction and radiation therapy to minimise surgical-related and radiation therapy-related morbidity (Cancer Council Australia Sarcoma Guidelines Working Party 2014).

The results of all relevant tests and imaging should be available for the multidisciplinary team discussion. The care coordinator or treating clinician should also present information about the patient’s concerns, preferences and social circumstances (Department of Health 2007c).

All patients with sarcoma should be offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial or clinical research if appropriate (Field et al. 2013).

Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

- Australasian Sarcoma Study Group is a national cooperative cancer clinical research group. It coordinates large-scale multi-centred sarcoma trials.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Cancer prehabilitation uses a multidisciplinary approach combining exercise, nutrition and psychological strategies to prepare patients for the challenges of cancer treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Evidence indicates that prehabilitating newly diagnosed patients with cancer before starting treatment can be beneficial. This may include conducting a physical and psychological assessment to establish a baseline function level, identifying impairments and providing targeted interventions to improve the patient’s health, thereby reducing the incidence and severity of current and future impairments related to cancer and its treatment (Silver & Baima 2013).

The process of prehabilitation for this complex group should be highly integrated with the treating surgical/medical team. Patients requiring amputation will benefit from preamputation counselling and comprehensive preoperative pain management to reduce the risk of phantom pain.

Medications should be reviewed at this point to ensure optimisation and to improve adherence to medicines used for comorbid conditions.

Screening with a validated screening tool (for example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the other common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include the following.

Physical

- Change in functional abilities – patients may benefit from referral to occupational therapy, physiotherapy and/or exercise physiology.

- Patient may need treatment for other physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and musculoskeletal dysfunction.

- Patients require ongoing nutritional screening, assessment and management. Reduced oral intake and/or swallowing difficulties and weight loss require referral to a dietitian and speech pathologist (for swallowing difficulties).

Psychological

- Patients may require help with psychological and emotional distress while adjusting to the diagnosis, treatment phobias, existential concerns, stress, difficulties making treatment decisions, anxiety/depression, psychosexual issues such as potential loss of fertility, loss of previous life roles and interpersonal problems.

Social/practical

- Patients may need support to attend appointments.

- Provide guidance about financial and employment issues (such as loss of income and having to deal with travel and accommodation requirements for rural patients and caring arrangements for other family members).

Information

- Discuss fertility options with the patient and/or family (where appropriate) before beginning treatment.

- Provide appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Spiritual needs

- Patients and their families should have access to spiritual support that is appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

The lead clinician should:

- establish if the patient has a regular or preferred general practitioner

- provide contact details of a key contact for the patient

- discuss a timeframe for diagnosis and treatment with the patient and carer

- discuss the option of fertility preservation (referral to a fertility service for counselling and evaluation of options may be appropriate)

- discuss the benefits of multidisciplinary care and make the patient aware that their health information will be available to the team for discussion at the multidisciplinary team meeting

- offer individualised sarcoma information that meets the needs of the patient and carer (this may involve advice from health professionals as well as written and visual resources)

- offer advice on how to access information and support from websites, community and national cancer services and support groups for both patients and carers

- refer the patient to the What to Expect – Sarcoma (bone and soft tissue tumours) guide.

- use a professionally trained interpreter to communicate with people from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The lead clinician should:

- ensure regular and timely (within a week) communication with the person’s general practitioner regarding the treatment plan and recommendations from multidisciplinary team meetings

- notify the general practitioner and family/carer if the person does not attend clinic appointments

- gather information from the general practitioner including their perspective on the person (psychological issues, social issues and comorbidities) and locally available support services

- help develop a chronic disease and mental healthcare plan as required

- discuss shared care arrangements (with general practitioners and/or regional cancer specialists)

- invite the general practitioner to participate in multidisciplinary team meetings (consider using video- or teleconferencing).

Step 4 outlines the treatment options for sarcoma. For detailed information on treatment options refer to the Cancer Council Australia Clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult onset sarcoma .

The intent of treatment can be defined as one of the following:

- curative

- anti-cancer therapy to improve quality of life and/or longevity without expectation of cure

- symptom palliation.

The morbidity and risks of treatment need to be balanced against the potential benefits.

The lead clinician should discuss treatment intent and prognosis with the patient and their family/ carer before beginning treatment.

Fertility preservation options should be discussed with the patient and/or family, where appropriate, before beginning treatment.

Advance care planning should be initiated with patients and their carers because there can be multiple benefits such as ensuring a person’s preferences are known and respected after the loss of decision-making capacity (AHMAC 2011).

The advantages and disadvantages of each treatment and associated potential side effects should be discussed with the patient and their carer/family.

Surgery is the most common treatment option for most types of sarcoma. This consists of resection and reconstruction.

The objective of surgical resection is to achieve adequate oncologic margins. Decisions about the optimal surgical procedure are made with reference to the tumour type, extent and response to neoadjuvant therapy if appropriate (refer to sections 4.2.2 and 4.2.3).

The objective of reconstruction is to promote wound healing, optimise function and improve the appearance of the affected area.

When surgery involves the limb, the preference is for limb salvage surgery, though occasionally ablative surgery (amputation) may be required.

Most patients are considered as candidates for limb salvage surgery. When considering the feasibility of limb preservation, the following should be taken into account:

- the outcome of surgery in regard to local recurrence

- distant metastasis and survival outcome (this should be comparable to that of ablative surgery)

- risk of complications

- possible re-operations and secondary amputation

- the functional outcome (this should be equivalent to or better than amputation).

All surgical options (including amputation) should be discussed with and acceptable to the patient.

It is important that the rehabilitation team has specific skills with limb salvage surgery and amputee rehabilitation. Upper limb amputees should receive rehabilitation as soon as possible after surgery.

Appropriate vascular and plastic surgical reconstructive options should be available.

Training, experience and treatment centre characteristics

The training and experience required of the surgeon is as follows:

- surgeon (FRACS or equivalent) with adequate training and experience and institutional cross- credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004)

- adequate training including subspecialty training at a national or international centre of excellence with continued practice as part of a recognised multidisciplinary team

- plastic surgeon with an interest and expertise in sarcoma reconstructive surgery.

Hospital or treatment unit characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- appropriate nursing and theatre resources to manage complex surgery

- theatre with prosthetics capability

- 24-hour medical staff availability

- 24-hour operating room access

- specialist pathology expertise / molecular pathology

- full anatomic imaging modalities

- specialist interventional diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine expertise.

Surgical volumes

High-volume centres generally have better clinical outcomes (Bhangu et al. 2004; Gutierrez et al. 2007; Sampo et al. 2012; Stiller et al. 2006) and are associated with improved rates of functional limb preservation, lower rates of local recurrence, good rates of overall survival and improved quality of life

(Cancer Council Australia Sarcoma Guidelines Working Party 2014). Centres that do not have sufficient caseloads should establish processes to routinely refer surgical cases to a high-volume centre.

All patients with large, localised, soft tissue tumours should be considered for radiation therapy by a radiation oncologist with experience in treating sarcomas and involvement in multidisciplinary care. For smaller tumors under 5 cm and lower grade tumours in more difficult anatomic sites, consideration should still be given to radiation therapy, given the implications of local recurrence in these anatomic sites (Pisters et al. 2016).

For soft tissue sarcoma, radiation therapy (external beam, brachytherapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, particle beam) must be considered before or after surgery.

The timing of radiation therapy needs to be individualised dependent upon resection and reconstructive considerations.

In general, radiation therapy for bone sarcomas is mainly used for palliation (ESMO 2014a). In Ewing’s sarcoma, radiation therapy may be considered as part of the treatment protocol.

Training, experience and treatment centre characteristics

Training and experience required of the appropriate specialist(s):

- radiation oncologist (Fellowship of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists or equivalent) with adequate training and experience with institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice in sarcoma (ACSQHC 2004)

- adequate training including subspecialty training at a national or international centre of excellence with continued practice as part of a recognised multidisciplinary team.

Radiation oncology centre characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- radiation therapists and medical physicists with experience in sarcoma care

- access to radiation therapy nurses, allied health professionals (especially for nutrition health and advice) occupational therapists and psychological support

- access to CT and MRI scanning for simulation and planning.

All patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma should be considered for protocolised pre- and/or postoperative chemotherapy by a medical oncologist with experience in treating sarcoma and involvement in multidisciplinary care (ESMO 2014a). Other forms of bone sarcomas should be treated as per multidisciplinary team discussion.

Rhabdomyosarcoma should be treated with protocolised pre- and/or postoperative chemotherapy by a medical oncologist with experience in treating sarcoma and involvement in multidisciplinary care.

For patients with other forms of localised soft tissue sarcoma, chemotherapy is not the current standard of care, and patients should be treated as per the multidisciplinary team’s treatment plan.

Training, experience and treatment centre characteristics

The following training and experience is required of the appropriate specialist(s):

- Medical oncologists (Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians or equivalent) must have adequate training and experience with institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004).

- Adequate training must include subspecialty training at a national or international centre of excellence with continued practice as part of a recognised multidisciplinary team.

- Nurses must have specialist training in chemotherapy handling, administration and disposal of cytotoxic waste and advanced understanding of chemotherapy toxicities. They must also have advanced central venous access knowledge and skills.

- Chemotherapy should be prepared by a pharmacist with adequate training in chemotherapy medication, including dosing calculations according to protocols, formulations and/or preparation.

- In a setting where no medical oncologist is locally available, some components of less complex therapies may be delivered by a medical practitioner and/or nurse with training and experience and with credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area under the guidance of a medical oncologist. This should be in accordance with a detailed treatment plan or agreed protocol and with communication as agreed with the medical oncologist or as clinically required.

Hospital or treatment unit characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- a clearly defined path to emergency care and advice after hours

- access to basic haematology and biochemistry testing

- cytotoxic drugs prepared in a pharmacy with appropriate facilities

- occupational health and safety guidelines regarding the handling of cytotoxic drugs, including safe prescribing, preparation, dispensing, supplying, administering, storing, manufacturing, compounding and monitoring the effects of medicines (ACSQHC 2011)

- guidelines and protocols regarding delivery treatment safely (including dealing with extravasation of drugs)

- mechanisms for coordinating combined therapy (chemotherapy and radiation therapy), especially where facilities are not collocated.

Timeframes should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce patient distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Sarcoma Working Group:3

- Patients must begin their treatment within three weeks of the decision to treat.

3 The multidisciplinary experts who participated in a clinical workshop to develop content for the sarcoma optimal care pathway are listed in the acknowledgements.

The lead clinician should ensure patients receive timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral should be based on need rather than prognosis.

- Patients may be referred to palliative care at initial diagnosis.

- Patients should be referred to palliative care at first recurrence or progression.

- Carer needs may prompt referral (Collins et al. 2013).

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014). This is particularly true for poor-prognosis cancers (Cancer Council Australia 2012; Philip et al. 2013; Temel et al. 2010). Furthermore, palliative care has been associated with improving the wellbeing of carers (Higginson & Evans 2010; Hudson et al. 2014).

Ensure carers and families receive information, support and guidance regarding their role according to their needs and wishes (Palliative Care Australia 2005).

The patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

All patients with sarcoma should be offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial or clinical research if appropriate (Field et al. 2013).

Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

- Australasian Sarcoma Study Group is a national cooperative cancer clinical research group. It coordinates large-scale multi-centred sarcoma trials.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit the Australian Cancer Trials website.

The lead clinician should discuss the patient’s use (or intended use) of complementary or alternative therapies not prescribed by the multidisciplinary team to identify any potential toxicity or drug interactions.

The lead clinician should seek a comprehensive list of all complementary and alternative medicines being taken and explore the patient’s reason for using these therapies and the evidence base.

Many alternative therapies and some complementary therapies have not been assessed for efficacy or safety. Some have been studied and found to be harmful or ineffective.

Some complementary therapies may assist in some cases and the treating team should be open to discussing the potential benefits for the individual.

If the patient expresses an interest in using complementary therapies, the lead clinician should consider referring them to health professionals within the multidisciplinary team who have knowledge of complementary and alternative therapies (such as a clinical pharmacist, dietitian or psychologist) to help them reach an informed decision.

The lead clinician should assure patients who use complementary or alternative therapies that they can still access multidisciplinary team reviews (NBCC & NCCI 2003) and encourage full disclosure about therapies being used (Cancer Australia 2010).

Further information

- See Cancer Australia’s position statement on complementary and alternative therapies.

- See the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia’s position statement.

Screening with a validated screening tool (for example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the other common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include the following.

Physical needs

- Decline in functional status (particularly as a result of limb reconstruction or amputation) may affect the patient’s mobility and ability to take part in everyday activities. Referral to an occupational therapist, orthotist/prosthetist and a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist for assessment, education, intervention and compensatory strategies may assist with maintaining mobility. Patients may require prolonged periods of rehabilitation.

- Healing of underlying structures, infection and other complication risks relating to skeletal implants may require input from wound nurse specialists and infection control specialists.

- Patients who have had a limb amputated to treat their sarcoma require rapid and easy access to prosthetic services.

- Treatment for other physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and musculoskeletal dysfunction may be required.

- Patients will require ongoing nutritional screening, assessment and management. Reduced oral intake and/or swallowing difficulties and weight loss require referral to a dietitian and speech pathologist (for swallowing difficulties).

- Assistance with managing complex medication regimens, multiple medications, assessing side effects and assistance with difficulties swallowing medications may be required. Refer to a pharmacist if necessary.

Psychological needs

- Disfigurement and scarring from appearance-altering treatment and the need for a prosthesis may require referral to a specialist psychologist, psychiatrist, orthotist/prosthetist or social worker.

- Patients may need support with emotional and psychological issues including, but not limited to, body image concerns, fatigue, existential anxiety, treatment phobias, anxiety/depression, psychosexual issues such as potential loss of fertility, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns.

Social/practical needs

- Ensure the patient attends appointments.

- Patients may experience isolation from their normal support networks, particularly for rural patients who are staying away from home for treatment.

- Financial issues related to loss of income and additional expenses as a result of illness and/or treatment may require support.

- Help with legal issues may be required including for advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability.

Information needs

- Provide appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Spiritual needs

- Multidisciplinary teams should have access to suitably qualified, authorised and appointed spiritual caregivers who can act as a resource for patients, carers and staff.

- Patients with cancer and their families should have access to spiritual support that is appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

The lead clinician should:

- offer advice to patients and carers on the benefits of or how to access support from sarcoma peer support groups, groups for carers and special interest groups

- discuss the treatment plan with the patient and carer, including the intent of treatment and expected outcomes

- provide the patient and carer with information on possible side effects of treatment, self-management strategies and emergency contacts

- recognise the ability of the patient and carers to comprehend the communication

- initiate a discussion regarding advance care planning with the patient and carer.

The lead clinician should:

- communicate with the person’s general practitioner about their role in symptom management, psychosocial care and referral to local services

- ensure regular and timely two-way communication regarding

- the treatment plan, including intent and potential side effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the patient’s prognosis and their understanding of this

- enrolment in research and/or clinical trials

- changes in treatment or medications

- recommendations from the multidisciplinary team.

The transition from active treatment to post-treatment care is critical to long-term health. After completing their initial treatment, patients should be provided with a treatment summary and follow- up care plan including a comprehensive list of issues identified by all members of the multidisciplinary team. The transition from acute to primary or community care will vary depending on the type and stage of cancer and therefore needs to be planned. In some cases, people will require ongoing, hospital-based care.

In the past two decades, the number of people surviving cancer has increased. International research shows there is an important need to focus on helping cancer survivors cope with life beyond their acute treatment. Cancer survivors experience particular issues, often different from patients having active treatment for cancer.

Many cancer survivors experience persisting side effects at the end of treatment. Emotional and psychological issues include distress, anxiety, depression, cognitive changes and fear of cancer recurrence. Late effects may occur months or years later and are dependent on the type of cancer treatment. Survivors may experience altered relationships and may encounter practical issues, including difficulties with return to work or study, and financial hardship.

Survivors generally need to see a doctor for regular follow-up, often for five or more years after cancer treatment finishes. The Institute of Medicine, in its report From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition, describes four essential components of survivorship care (Hewitt et al. 2006):

- the prevention of recurrent and new cancers, as well as late effects

- surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence or second cancers, and screening and assessment for medical and psychosocial late effects

- interventions to deal with the consequences of cancer and cancer treatments (including manageing symptoms, distress and practical issues)

- coordination of care between all providers to ensure the patient’s needs are met.

All patients should be educated in managing their own health needs (NCSI 2015).

After initial treatment, the patient, their carer (as appropriate) and general practitioner should receive a treatment summary outlining:

- the diagnostic tests performed and results

- tumour characteristics

- the type and date of treatment(s)

- interventions and treatment plans from other health professionals

- supportive care services provided

- contact information for key care providers.

Care in the post-treatment phase is driven by predicted risks (such as the risk of recurrence, developing late effects and psychological issues), as well as individual clinical and supportive care needs.

Responsibility for follow-up care should be agreed between the lead clinician, the general practitioner, relevant members of the multidisciplinary team and the patient, with an agreed plan that outlines:

- what medical follow-up is required (surveillance for recurrence, screening and assessment for medical and psychosocial effects)

- care plans from other health professionals to manage the consequences of cancer and treatment (including assessing psychological distress)

- a process for rapid re-entry to specialist medical services for suspected recurrence

- the role of follow-up for patients, which is to evaluate tumour control, monitor and manage symptoms from the tumour and treatment and provide psychological support

- that they will be retained within the multidisciplinary team management framework.

Follow-up should include access to a range of health professions (if required) including physiotherapy, orthotics, exercise physiology, occupational therapy, nursing, social work, dietetics, psychology and palliative care (in the hospital or community setting).

Specialist team surveillance should include:

- regular clinical examination and routine surveillance for local recurrence

- assessing function and possible complications from any reconstruction

- imaging (includes MRI, CT and functional imaging such as PET, thallium or technetium bone scan)

These should be conducted at the following intervals:

- three- to four-monthly for two years, then six-monthly for two years and yearly thereafter for four years – giving a total of eight years of follow-up for patients with fully resected disease.

- In cases where additional surveillance is required, the timing and frequency will be discussed on its merits.

- Patients should be referred from paediatric services to adult services as they transition between paediatric and adult age groups.

All patients with sarcoma should be offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial or clinical research if appropriate (Field et al. 2013).

Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

- Australasian Sarcoma Study Group is a national cooperative cancer clinical research group.

- It coordinates large-scale multi-centred sarcoma trials.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit the Australian Cancer Trials website.

Screening with a validated screening tool (for example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the other common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include the following.

Physical needs

- Upper and lower limb lymphoedema may require referral to a trained lymphoedema practitioner.

- Long-term phantom limb pain may require ongoing pain management.

- Decline in functional status (particularly from limb reconstruction or amputation) may affect the patient’s mobility and ability to take part in everyday activities. Referral to an occupational therapist, orthotist/prosthetist and a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist for assessment, education, intervention and compensatory strategies may assist with maintaining mobility. These may require prolonged periods of rehabilitation.

- Healing of underlying structures, infection and other complication risks relating to skeletal implants may require input from wound nurse specialists and infection control specialists.

- Patients require ongoing nutritional screening, assessment and management. Reduced oral intake and/or swallowing difficulties and weight loss require referral to a dietitian and speech pathologist (for swallowing difficulties).

- Patients may need treatment for other physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and musculoskeletal dysfunction.

Psychological needs

- Disfigurement and scarring from appearance-altering treatment and the need for a prosthesis may require referral to a specialist psychologist, psychiatrist, orthotist/prosthetist or social worker.

- Patients may need support with emotional and psychological issues including, but not limited to, body image concerns, fatigue, existential anxiety, treatment phobias, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns.

Social/practical needs

- Ensure the patient attends appointments.

- Financial issues related to loss of income and additional expenses as a result of illness and/or treatment may require support.

- Help with legal issues may be required including for advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability.

Information needs

- Provide appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Spiritual needs

- Patients with cancer and their families should have access to spiritual support that is appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

Rehabilitation may be required at any point of the care pathway from preparing for treatment through to disease-free survival and palliative care.

Evaluation for postoperative rehabilitation is recommended for all patients with extremity sarcoma (NCCN 2016a, NCCN 2016b). Amputees should be referred to a specialist physiotherapist for a comprehensive rehabilitation program. Rehabilitation should be continued until maximum function is achieved (NCCN 2016a) and should be highly integrated with the treating medical team.

Other issues that may need to be addressed include managing cancer-related fatigue, cognitive changes, improving physical endurance, achieving independence in daily tasks, returning to work and ongoing adjustment to disease and its sequelae.

The lead clinician should ensure patients receive timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral should be based on need rather than prognosis.

- Patients may be referred to palliative care at initial diagnosis.

- Patients should be referred to palliative care at first recurrence or progression.

- Carer needs may prompt referral (Collins et al. 2013).

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014). This is particularly true for poor-prognosis cancers (Cancer Council Australia 2012; Philip et al. 2013; Temel et al. 2010). Furthermore, palliative care has been associated with the improved wellbeing of carers (Higginson 2010; Hudson et al. 2014).

Ensure carers and families receive information, support and guidance regarding their role according to their needs and wishes (Palliative Care Australia 2005).

The patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

The lead clinician should:

- offer advice to patients and carers on the benefits of or how to access support from sarcoma peer support groups, groups for carers and special interest groups

- explain the treatment summary and follow-up care plan

- provide information about the signs and symptoms of recurrent disease

- provide information about healthy living.

The lead clinician should ensure regular, timely, two-way communication with the patient’s general practitioner regarding:

- the follow-up care plan

- potential late effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the patient’s progress

- recommendations from the multidisciplinary team

- any shared care arrangements.

Step 6 is concerned with managing recurrent, residual or metastatic disease.

Between 30 and 40 per cent of all patients with sarcomas develop local or distant recurrence (Cancer Council Australia Sarcoma Guidelines Working Party 2014). The risk of recurrence is greatest in the first few years, with approximately two out of three recurrences developing within two years and 95 per cent by five years (of initial diagnosis). Diagnoses can be stratified into risk groups based on the prognostic features of the primary tumour (Cancer Council Australia Sarcoma Guidelines Working Party 2014).

In those patients with recurrent or residual disease there should be timely referral to the original multidisciplinary team (where possible) and thereby quick access to specialist input into care.

The pathway for and manageing patients with recurrent or metastatic sarcoma is a continuum of care within the multidisciplinary team and recapitulates section 4.

Treatment will depend on the location and extent of disease, timing of recurrence, previous management and the patient’s preferences.

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate.

The standard approach to local recurrence parallels the approach to primary local disease, although more often resort to preoperative or postoperative radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy, if not previously carried out.

In the case of isolated lung metastases, treatment is primarily surgical where complete removal of all metastases should be attempted (ESMO 2014a).

Palliative radiation therapy or chemotherapy may be considered for inoperable metastases (ESMO 2014a).

A number of targeted therapies have shown promising results in patients with certain histological types of advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (NCCN 2016a). The role of chemotherapy for recurrent Ewing’s sarcoma and osteosarcoma should follow protocolised treatment following multidisciplinary team discussion.

The lead clinician should ensure patients receive timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral should be based on need rather than prognosis.

- Patients may be referred to palliative care at initial diagnosis.

- Patients should be referred to palliative care at the first recurrence or progression.

- Carer needs may prompt referral.

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014). This is particularly true for poor-prognosis cancers (Temel et al. 2010). Furthermore, palliative care has been associated with the improved wellbeing of carers (Higginson & Evans 2010; Hudson et al. 2015).

Ensure carers and families receive information, support and guidance regarding their role according to their needs and wishes (Palliative Care Australia 2005).

The patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011). For more information refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate.

- Australasian Sarcoma Study Group is a national cooperative cancer clinical research group. It coordinates large-scale multi-centred sarcoma trials.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit the Australian Cancer Trials website.

Screening with a validated screening tool (such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals and/or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific issues that may arise include the following.

Physical needs

- Patients may require treatment for ongoing/new physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and musculoskeletal dysfunction.

- Patients require ongoing nutritional screening, assessment and management. Reduced oral intake and/or swallowing difficulties and weight loss require referral to a dietitian and speech pathologist (for swallowing difficulties).

- Assistance with managing complex medication regimens, multiple medications, assessing side effects and assistance with difficulties swallowing medications may be required. Refer to a pharmacist if necessary.

Psychological needs

- Emotional and psychological distress may result from fear of death, complications of chemotherapy, existential concerns, anticipatory grief, communicating wishes to loved ones, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns.

Social/practical needs

- Ensure the patient attends appointments.

- Patients may experience isolation from their normal support networks, particularly for rural patients who are staying away from home for treatment.

- Financial issues may result from disease recurrence (patients may need early access to superannuation and insurance).

- Help with legal issues may be required including for advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability.

Information needs

- Provide appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Spiritual needs

- Multidisciplinary teams should have access to suitably qualified, authorised and appointed spiritual caregivers who can act as a resource for patients, carers and staff.

- Patients with cancer and their families should have access to spiritual support that is appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

Rehabilitation may be required at any point of the care pathway, from preparing for treatment through to disease-free survival and palliative care. Issues that may need to be addressed include managing cancer-related fatigue, cognitive changes, improving physical endurance, achieving independence in daily tasks, returning to work and ongoing adjustment to disease and its sequelae.

The lead clinician should ensure there is adequate discussion with the patient and carer about the diagnosis and recommended treatment, including the intent of treatment and its possible outcomes, likely adverse effects and supportive care options available for both the patient and their family/carer.

End-of-life care is appropriate when the patient’s symptoms are increasing and functional status is declining. Step 7 is concerned with maintaining the patient’s quality of life and addressing their health and supportive care needs as they approach the end of life, as well as the needs of their family and carer. Consideration of appropriate venues of care is essential. The principles of a palliative approach to care need to be shared by the team when making decisions with the patient and their family.

If not already underway, referral to palliative care should be considered at this stage (including nursing, pastoral care, palliative medicine specialist backup, inpatient palliative bed access as required, social work, psychology/psychiatry and bereavement counselling), with general practitioner engagement.

If not already in place, the patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

The palliative care team may consider seeking additional expertise from a:

- pain service

- pastoral carer or spiritual advisor

- bereavement counsellor

- therapist (for example, music or art).

The team might also recommend accessing:

- a respite specialist

- home- and community-based care

- specialist community palliative care workers

- community nursing.

Consideration of an appropriate place of care and preferred place of death is essential.

Occupational therapy home assessment is also essential to ensure palliative patients receiving home-based care are managed safely.

Ensure carers and families receive information, support and guidance regarding their role according to their needs and wishes (Palliative Care Australia 2005).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

All patients with sarcoma should be offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial or clinical research if appropriate (Field et al. 2013).

Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

- Australasian Sarcoma Study Group is a national cooperative cancer clinical research group.

- It coordinates large-scale multi-centred sarcoma trials.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit the Australian Cancer Trials website.

Screening with a validated screening tool (for example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the other common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include the following.

Physical needs

- Physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue and musculoskeletal dysfunction may require extra support.

- Decline in mobility and/or functional status affecting the patient’s discharge destination will need to be considered.

- Fatigue or change in functional abilities is a common symptom, and patients may benefit from referral to occupational therapy and/or physiotherapy.

- Reduced oral intake and/or swallowing difficulties and weight loss require referral to a dietitian and speech pathologist (for swallowing difficulties).

Psychological needs

- Patients, carers and families may need strategies to deal with emotional and psychological distress from anticipatory grief, fear of death/dying, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems and anticipatory bereavement support.

- Patients who experience existential distress may benefit from supportive psychotherapy.

Social/practical needs

- Provide support for the practical, financial and impacts on carers and family members resulting from the increased care needs of the patient.

- Offer specific support for families where a parent is dying and will leave behind bereaved children or adolescents, creating special family needs.

- Ensure the patient attends appointments.

- Patients may experience isolation from their normal support networks, particularly for rural patients who are staying away from home for treatment.

- Provide support for financial issues related to loss of income and additional expenses because of the illness and/or treatment.

- Help with legal issues may be required including for advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability.

Information needs

- Provide information for patients and families about arranging a funeral.

- Communicate about the death and dying process and what to expect.

- Communicate with all members of the care team that the patient has died.

- Provide appropriate information for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Spiritual needs

- Cater to specific spiritual needs that may benefit from involving pastoral care.

- Provide bereavement support for family and friends.

- Multidisciplinary teams should have access to suitably qualified, authorised and appointed spiritual caregivers who can act as a resource for patients, carers and staff.

- Patients with cancer and their families should have access to spiritual support that is appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

The lead clinician should:

- be open to and encourage discussion about the expected disease course, with due consideration to personal and cultural beliefs and expectations

- discuss palliative care options including inpatient and community-based services as well as dying at home and subsequent arrangements

- provide the patient and carer with the contact details of a palliative care service.

The lead clinician should discuss end-of-life care planning and transition planning to ensure the patient’s needs and goals are addressed in the appropriate environment. The patient’s general practitioner should be kept fully informed and involved in major developments in the patient’s illness trajectory.

Planning and delivering appropriate cancer care for older people presents a number of challenges. Improved communication between the fields of oncology and geriatrics facilitates best practice care that takes into account physiological age, complex comorbidities, risk of adverse events and drug interactions, as well as implications of cognitive impairment on suitability of treatment and consent (Steer et al. 2009).

A national interdisciplinary workshop convened by the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) recommended that people over the age of 70 undergo some form of geriatric assessment in line with international guidelines (COSA 2013). Assessment can be used to determine life expectancy and treatment tolerance as well as identifying conditions that might interfere with treatment including:

- cognition

- comorbidity

- emotional status

- function

- nutrition

- polypharmacy

- presence of geriatric syndromes

- social supports.

Guided intervention using aged care services is appropriate.

The rarity and complexity of child cancer provides a real challenge in delivering optimal care. Treatment modalities for paediatric cancer are often prolonged and complicated and have a narrow therapeutic index. Side effects of systemic therapy for treating cancer can be more severe for children, including acute organ toxicities, prolonged immunodeficiency and infection.

As a result of these complexities, high-quality evidence-based care is required not only to deliver therapy and supportive care but is essential in the diagnosis phase, post-treatment surveillance and long-term follow-up care. Children with sarcoma must have their treatment delivered by a statewide referral centre for paediatric oncology. Consider shared care for surveillance once treatment is completed. Children’s cancer services actively participate in clinical trials as a way of participating in research and improving outcomes for children.

Recent years have seen the emergence of adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology as a distinct field due to lack of progress in survival and quality-of-life outcomes (Ferrari et al. 2010; NCI & USDHHS 2006; Smith et al. 2013). The significant developmental change that occurs during this life stage complicates a diagnosis of cancer during the AYA years, often leading to unique physical, social and emotional impacts for young people at the time of diagnosis and throughout the cancer journey (Smith et al. 2012).

In caring for young people with cancer, pay careful attention to promoting normal development (COSA 2011). This requires personalised assessments and management involving a multidisciplinary, disease-specific, developmentally targeted approach informed by:

- understanding the developmental stages of adolescence and supporting normal adolescent health and development alongside cancer management

- understanding and supporting the rights of young people

- communication skills and information delivery that are appropriate to the young person

- addressing the needs of all involved, including the young person, their family and/or carer(s)

- working with educational institutions and workplaces

- addressing survivorship and palliative care needs.

- An oncology team caring for a young person with cancer must:

- ensure access to expert AYA health professionals who understand the biomedical and psychosocial needs of the population

- understand the biology and current management of the disease in the AYA age group

- consider clinical trials accessibility and recruitment for each patient

- engage in proactive discussions about fertility preservation and the late effects of treatment and consider the patient’s psychosocial needs

- provide treatment in an AYA-friendly environment.

The burden of cancer is higher in the Australian Indigenous population (AIHW 2014). Survival also significantly decreases as remoteness increases, unlike the survivorship rates of non-Indigenous Australians. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have high rates of certain lifestyle risk factors including tobacco smoking, higher alcohol consumption, poor diet and low levels of physical activity (Cancer Australia 2015). The high prevalence of these risk factors is believed to be a significant contributing factor to the patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates in this population group (Robotin et al. 2008).

In caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people diagnosed with cancer, the current gap in survivorship is a significant issue. The following approaches are recommended to improve survivorship outcomes (Cancer Australia 2013):

- Raise awareness of risk factors and deliver key cancer messages.

- Develop evidence-based information and resources for community and health professionals.

- Provide training for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers and develop training resources.

- Increase understanding of barriers to care and support.

- Encourage and fund research.

- Improve knowledge within the community to act on cancer risk and symptoms.

- Improve the capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers to provide cancer care and support to their communities.

- Improve system responsiveness to cultural needs.

- Improve our understanding of care gaps through data monitoring and targeted priority research.

For people from diverse backgrounds in Australia, a cancer diagnosis can come with additional complexities, particularly when English proficiency is poor. In some languages there is not a direct translation of the word ‘cancer’, which can make communicating vital information difficult.