Cervical cancer

The optimal care pathway is intended to guide the delivery of consistent, safe, high-quality and evidence-based care for women with cancer.

The pathway aligns with key service improvement priorities including providing access to coordinated multidisciplinary care and supportive care and reducing unwanted variation in practice.

The optimal care pathway can be used by health services and professionals as a tool to identify gaps in current cancer services and to inform quality improvement initiatives across all aspects of the care pathway. The pathway can also be used by clinicians as an information resource and tool to promote discussion and collaboration between health professionals and people affected by cancer.

The following key principles of care underpin the optimal care pathway.

Patient-centred care

Patient- or consumer-centred care is healthcare that is respectful of, and responsive to, the preferences, needs and values of patients and consumers. Patient- or consumer-centred care is increasingly being recognised as a dimension of high-quality healthcare in its own right, and there is strong evidence that a patient-centred focus can lead to improvements in healthcare quality and

outcomes by increasing safety and cost-effectiveness as well as patient, family and staff satisfaction (ACSQHC 2013).

Safe and quality care

Safe and quality care is provided by appropriately trained and credentialled clinicians, hospitals and clinics that have the equipment and staffing capacity to support safe and high-quality care. It incorporates collecting and evaluating treatment and outcome data to improve a woman’s experience of care as well as mechanisms for ongoing service evaluation and development to ensure practice remains current and informed by evidence.

Multidisciplinary care

Multidisciplinary care is an integrated team approach to health care in which medical and allied health professionals consider all relevant treatment options and collaboratively develop an individual treatment and care plan for each woman. There is increasing evidence that multidisciplinary care improves patient outcomes.

The benefits of adopting a multidisciplinary approach include:

- improving patient care through developing an agreed treatment plan

- providing best practice through adopting evidence-based guidelines

- improving patient satisfaction with treatment

- improving the mental wellbeing of patients

- improving access to possible clinical trials

- increasing the timeliness of appropriate consultations and surgery and a shorter timeframe from diagnosis to treatment

- increasing the access to timely supportive and palliative care

- streamlining pathways

- reducing duplication of services (Department of Health 2007b).

Supportive care

Supportive care is an umbrella term used to refer to services, both generalist and specialist, that may be required by those affected by cancer. Supportive care addresses a wide range of needs across the continuum of care and is increasingly seen as a core component of evidence-based clinical care. Palliative care can be part of supportive care processes. Supportive care in cancer refers to the following five domains:

- physical needs

- psychological needs

- social needs

- information needs

- spiritual needs.

All members of the multidisciplinary team have a role in providing supportive care. In addition, support from family, friends, support groups, volunteers and other community-based organisations make an important contribution to supportive care.

An important step in providing supportive care is to identify, by routine and systematic screening (using a validated screening tool such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist) of the woman and family, views on issues they require help with for optimal health and quality-of-life outcomes. This should occur at key points along the care pathway, particularly at times of increased vulnerability including:

- initial presentation or diagnosis (first three months)

- the beginning of treatment or a new phase of treatment

- change in treatment

- change in prognosis

- end of treatment

- survivorship

- recurrence

- change in or development of new symptoms

- palliative care

- end-of-life care.

Following each assessment, potential interventions need to be discussed with the woman and carer and a mutually agreed approach to multidisciplinary care and supportive care formulated (NICE 2004).

Common indicators in women with cervical cancer that may require referral for support include:

- malnutrition (as identified using a validated malnutrition screening tool or presenting with weight loss)

- breathlessness

- pain

- difficulty managing fatigue

- difficulty sleeping

- distress, depression or fear

- poor performance status

- living alone or being socially isolated

- having caring responsibilities for others

- cumulative stressful life events

- existing mental health issues

- having a disability

- Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status

- being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background

- concerns regarding fertility, sexuality and menopause psychosexual problems.

Depending on the needs of the woman, referral to an appropriate health professional(s) and/or organisation(s) should be considered including:

- a psychologist or psychiatrist

- community-based support services (such as Cancer Council)

- a dietitian

- an exercise physiologist

- a gastroenterologist

- nurse practitioner or specialist nurse

- an occupational therapist

- a physiotherapist

- peer support groups (contact Cancer Council on 13 11 20 for more information)

- a social worker

- specialist palliative care.

See the Appendix for more information on supportive care and the specific needs of women with cervical cancer.

Care coordination

Care coordination is a comprehensive approach to achieving continuity of care for patients. This approach seeks to ensure that care is delivered in a logical, connected and timely manner so the medical and personal needs of the woman are met.

In the context of cancer, care coordination encompasses multiple aspects of care delivery including multidisciplinary team meetings, supportive care screening/assessment, referral practices, data collection, development of common protocols, information provision and individual clinical treatment.

Improving care coordination is the responsibility of all health professionals involved in the care of patients and should therefore be considered in their practice. Enhancing continuity of care across the health sector requires a wholeof-system response – that is, that initiatives to address continuity of care occur at the health system, service, team and individual levels (Department of Health 2007c).

Communication

It is the responsibility of the healthcare system and all people within its employ to ensure the communication needs of patients, their families and carers are met. Every person with cancer will have different communication needs, including cultural and language differences. Communication with patients should be:

- individualised

- truthful and transparent, though handled with sensitivity

- consistent

- in plain language (avoiding complex medical terms and jargon)

- culturally sensitive

- active, interactive and proactive

- ongoing

- delivered in an appropriate setting and context

- inclusive of patients and their families.

In communicating with patients, healthcare providers should:

- listen to patients and act on the information provided by them

- encourage expression of individual concerns, needs and emotional states

- tailor information to meet the needs of the woman, their carer and family

- use professionally trained interpreters when communicating with patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- ensure the woman and/or their carer and family have the opportunity to ask questions

- ensure the woman is not the conduit of information between areas of care (it is the provider’s and healthcare system’s responsibility to transfer information between areas of care)

- take responsibility for communication with the woman

- respond to questions in a way the woman understands

- enable all communication to be two-way.

Healthcare providers should also consider offering the woman a Question Prompt List (QPL) in advance of their consultation, and recordings or written summaries of their consultations. QPL interventions are effective in improving the communication, psychological and cognitive outcomes of cancer patients (Brandes et al. 2014). Providing recordings or summaries of key consultations may improve the patient’s recall of information and patient satisfaction (Pitkethly et al. 2008).

Research and clinical trials

Where practical, patients should be offered the opportunity to participate in research and/or clinical trials at any stage of the care pathway. Research and clinical trials play an important role in

establishing efficacy and safety for a range of treatment interventions, as well as establishing the role of psychological, supportive care and palliative care interventions (Sjoquist & Zalcberg 2013).

While individual patients may or may not receive a personal benefit from the intervention, there is evidence that outcomes for participants in research and clinical trials are generally improved, perhaps due to the rigour of the process required by the trial. Leading cancer agencies often recommend participation in research and clinical trials as an important part of patient care. Even in the absence of a measurable benefit to patients, participating in research and clinical trials will contribute to the care of cancer patients in the future (Peppercorn et al. 2004).

Timeframes to treatment: Timeframes should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce women’s distress. The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Cervical Cancer Working Group.

Timeframes for care

| Step in pathway | Care point | Timeframe |

| Presentation, initial investigations and referral | 2.1 Assessments by the general or primary medical practitioner | Screening test results should be available and the woman reviewed by the general practitioner within 30 days |

| 2.2 Referral to a specialist | • Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (any type) test result and reflex liquid-based cytology (LBC) report of invasive cancer

should have a specialist appointment with a gynaecological oncologist within two weeks of the suspected diagnosis • Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (16/18) test result and reflex LBC prediction of any abnormality should be referred for a colposcopic assessment within eight weeks • Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) test result, with a LBC prediction of pHSIL/HSIL or any glandular abnormality, should be referred for a colposcopic assessment within eight weeks • Women with a suspected diagnosis of cervical cancer (symptomatic, abnormal cervix) should have a specialist appointment with a gynaecological oncologist within two weeks of the suspected diagnosis |

|

| Diagnosis, staging and treatment planning | 3.1 Diagnostic work-up | • For obvious abnormalities, a colposcopy within two weeks of referral

• Diagnostic investigations should be completed within two weeks of specialist review |

| 3.3.1 The optimal timing for multidisciplinary team planning | All newly diagnosed women should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting so a treatment plan can be recommended | |

| Treatment | 4.2.1 Surgery for primary disease | Treatment should begin within four weeks of the decision to treat |

| 4.2.2 Radiation therapy | Treatment should begin within four weeks of the decision to treat | |

| 4.2.3 Chemotherapy | Treatment should begin within four weeks of the decision to treat |

The optimal care pathway outlines seven critical steps in the patient journey. While the seven steps appear in a linear model, in practice, patient care does not always occur in this way but depends on the particular situation (such as the type of cancer, when and how the cancer is diagnosed, prognosis, management, the woman’s decisions and the woman’s physiological response to treatment).

The pathway describes the optimal cancer care that should be provided at each step. The pathway includes all squamous cell, glandular (adeno) and mixed-cell cervical carcinomas. Squamous cell carcinomas account for 65–70 per cent of cervical cancers, and adenocarcinomas account for 20–25 per cent (AIHW 2018).

Rare histologies such as neuroendocrine, melanoma and serous are outside the scope of this optimal care pathway.

‘Women’ is the general term used throughout this optimal care pathway; however, the advice in this pathway also applies to all people who have a cervix including transgender and intersex people.

In Australia cervical cancer accounts for less than two per cent of all female cancers, with a relatively low incidence of seven new cases per 100,000 women per year (AIHW 2017).

A healthy diet, avoiding or limiting alcohol intake, taking regular exercise and maintaining a healthy body weight may help reduce cancer risk. This step outlines recommendations for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer.

The number of new cases of cervical cancer is likely to be dramatically reduced as the benefits of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination are realised (Hall et al. 2018). It is likely that in the future, cervical cancer will largely (but not exclusively) be confined to women who have not been immunised, or for whom immunisation comes well after exposure to HPV.

Three HPV vaccines are registered for use in Australia – Gardasil, Gardasil 9 and Cervarix. All three vaccines protect against the two high risk HPV types (16 and 18) which are associated with around 70 per cent of cervical cancers in Australian women. Gardasil and Gardasil 9 also protect against two low risk HPV types (6 and 11), which cause 90% of genital warts (Cancer Council Australia, 2017). Gardasil 9 replaced Gardasil on the National Immunisation Program in January 2018, Gardasil 9 commenced use in the NHVP program for 12 and 13-year-old girls and boys. This is protecting against an additional five strains of HPV (31, 33, 45, 52 and 58), and predicted to further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer (Simms K T el al 2016). HPV vaccination is delivered via a school-based program to adolescent females and males in years 7 or 8 (i.e. aged 12 to 13 years) as part of the National Immunisation Program, with a catch up program available to individuals (females and males) up to the age of 19 years.

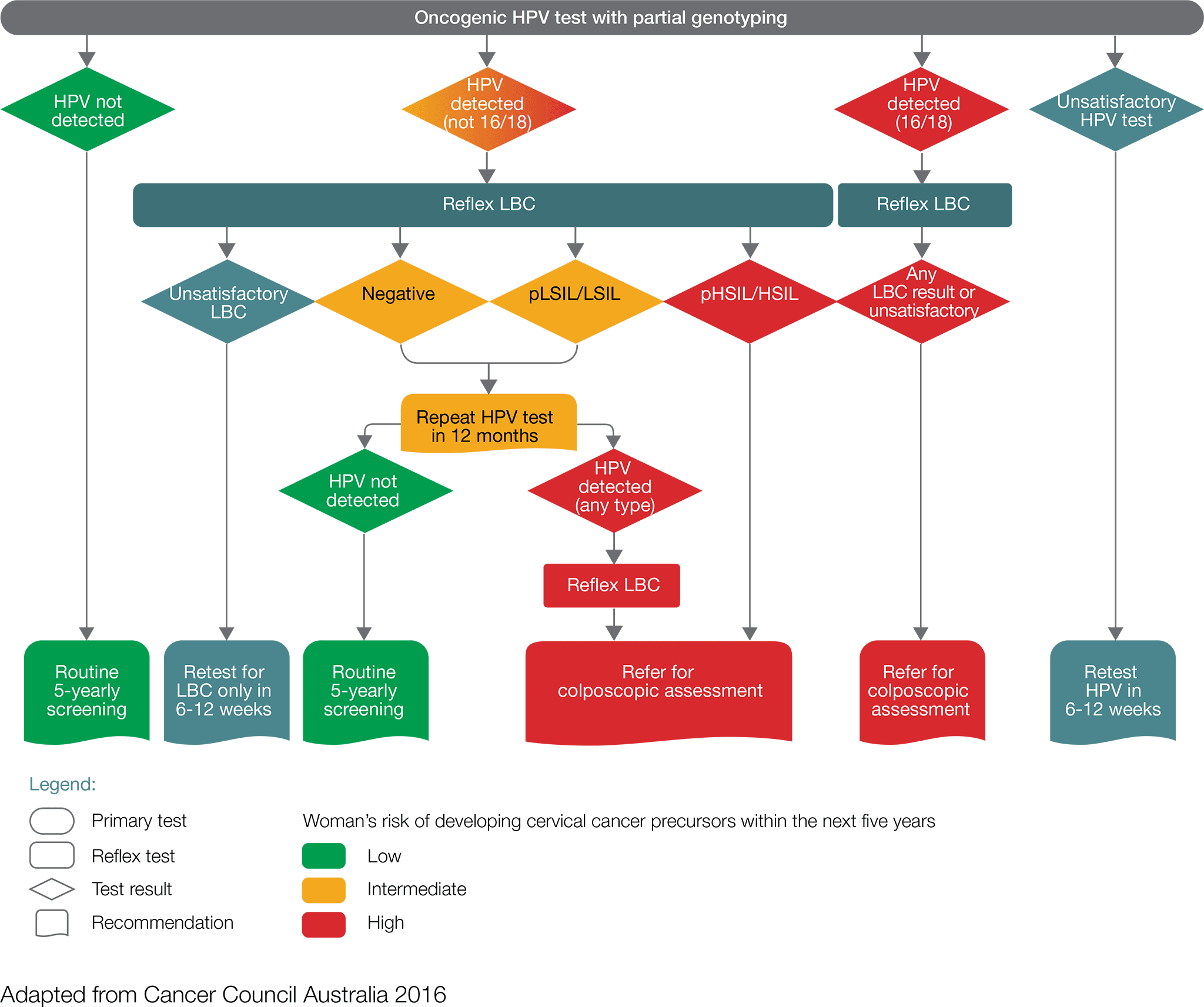

The National Cervical Screening Program aims to prevent cervical cancer by detecting early changes in the cervix. A five-yearly HPV test for women aged 25–74 years began on 1 December 2017 to replace the previous two-yearly Pap test for women aged 18–69 years. The cervical screening test checks for the presence of HPV, the causal agent for most cervical cancers (Australian Government Department of Health 2017).

Self-sampling is available to women at least 30 years of age and who are considered under- screened (four or more years since last Pap test), or who have never been screened and who decline a practitioner-collected specimen. Self-collection is a vaginal swab for HPV testing.

HPV-vaccinated women still require cervical screening tests because the HPV vaccine does not protect against all the types of HPV that cause cervical cancer.

Primary health practitioners, including general practitioners and nurses, play a crucial role in encouraging women to screen regularly.

For more information refer to the 2016 guidelines: The National Cervical Screening Program: guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities, screening in specific populations and investigation of abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Long-term infection with certain types of HPV is known to be the cause of most cervical cancers. HPV is a common virus, with four out of five people having HPV at some time in their lives (Australian Government Department of Health 2017). In most cases, the infection is transient, but in rare cases, if the virus persists (usually over a 10-year period) and if left undetected, can lead to cervical cancer.

Currently the best protection against progressing to a cervical cancer is participating in regular cervical screening (Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry 2017).

Certain groups are less likely to access cervical screening and therefore are at higher risk. Vulnerable groups include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and culturally and linguistically diverse populations. For more information refer to the National Cervical Screening Program toolkit for engaging under-screened and never-screened women.

Other risk factors include:

- smoking

- previous abnormality or cancer of the cervix

- having many children

- exposure to diethylstilboestrol (DES) (Cancer Australia 2017)

- taking contraceptive pills for a long time

- being HIV positive

- being immunocompromised or taking immunosuppressive medication (Cancer Research UK 2014; Ngyuyen & Flowers 2013).

Cervical cancer is one of the most preventable cancers through HPV immunisation and regular cervical screening.

In Australia, women with disabilities are under-screened for cervical cancer compared with Australians without a disability (Department of Health and Human Services 2013). Barriers include physical limitations, competing health needs that require more urgent medical attention, the trauma of undergoing an invasive test, and lack of information. Assumptions that all women with disabilities are not sexually active also need to be addressed.

Rape victims and survivors of previous sexual abuse may also need additional support, including issues around disclosure of past history of sexual abuse or trauma.

The following approaches are recommended to promote participation and improve the experience of cervical screening:

- Consider reasonable adjustments, including alternative pathways, such as self-collection.

- Consider informed consent and the potential barriers associated with obtaining this, particularly if a power of attorney lies with a family member or carer.

- Encourage women to bring a support person with them to appointments.

- For women with disabilities, encourage use of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare disability flag at the point of admittance, and note any disabilities in referral forms to diagnostic assessment.

- Ensure facilities actively address the access requirements of people with disabilities.

- Consider catch-up HPV vaccination if appropriate.

This step outlines the process for establishing a diagnosis and appropriate referral. The types of investigation undertaken by the general or primary practitioner depend on many factors including access to diagnostic tests, medical specialists and the woman’s preferences.

General practitioners play a crucial role in encouraging women to screen regularly.

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (16/18) test result including those found through a self-collected sample should be referred directly for a colposcopic assessment, which will be informed by the result of reflex liquid-based cytology (LBC).

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) test result, with an LBC report of possible high-grade lesion or high-grade lesion should be referred directly for colposcopic assessment

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) test result, with an LBC report of negative or low-grade lesion, should have a repeat HPV test in 12 months.

- For women with a self-collected positive oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) they should be advised to visit their GP or healthcare professional to obtain a cervical sample for liquid-based cytology. If the liquid-based cytology result is possible high-grade or high-grade, the women should be referred for colposcopy ideally within 8 weeks.

At 12 months, repeat HPV testing:

- Women in whom oncogenic HPV is not detected should return to routine five-yearly clinician- collected screening.

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (any type) test result should be referred for a colposcopic assessment. If the repeat HPV test was self-collected, a cervical sample for LBC should be obtained at the time of the colposcopy.

While general practitioners recommendations will be informed by the results of the two tests (HPV test and LBC), a negative test should not preclude further investigations of signs and symptoms that suggest the presence of cervical cancer.

If a woman presents with symptoms at any age, whether or not she has been vaccinated against HPV, the symptoms should be investigated.

In the early stages of cervical cancer, there may be no symptoms at all. If symptoms occur, they commonly include:

- postcoital bleeding

- intermenstrual bleeding

- postmenopausal bleeding

- dyspareunia

- unusual or watery vaginal discharge.

Symptoms of advanced cervical cancer include:

- pelvic pain

- extreme fatigue

- kidney failure

- leg pain or swelling

- lower back pain.

At the time of specialist referral, an assessment informed by signs and symptoms, including a physical examination, co-test (simultaneous HPV and LBC tests), and blood tests (FBE) should occur. If the cervix appears abnormal (suspicious for cancer) on physical examination consider direct referral to a specialist gynaecological oncologist who is part of a multidisciplinary team. Where there is not an obvious cancer the flowchart should guide management.

If the diagnosis is suspected or confirmed with initial tests, then referral to a certified gynaecological oncologist who is a member of a multidisciplinary team is optimal.

Referral should include relevant past history, current history, family history, examination, investigations, psychosocial issues and current medications.

Timeframes should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce the woman’s distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Cervical Cancer Working Group(1):

- Cervical testing results should be available and the woman reviewed by her general practitioner within 30 days.

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (any type) test result and LBC report of invasive cancer should have a specialist appointment with a gynaecological oncologist within two weeks of the suspected diagnosis.

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (16/18) test result and reflex LBC prediction of any abnormality should be referred for a colposcopic assessment within eight weeks.

- Women with a positive oncogenic HPV (not 16/18) test result, with a LBC prediction of pHSIL/HSIL or any glandular abnormality, should be referred for a colposcopic assessment within eight weeks.

- Women with a suspected diagnosis of cervical cancer (symptomatic, abnormal cervix) should have a specialist appointment with a gynaecological oncologist within two weeks of the suspected diagnosis.

The supportive and liaison role of the general practitioner and practice team in this process is critical.

1: The multidisciplinary experts group who participated in a clinical workshop to develop content for the cervical cancer optimal care pathway are listed in the acknowledgements list.

An individualised clinical assessment is required to meet the identified needs of the woman, her carer and family; referral should be as required.

In addition to common issues identified in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include:

- treatment for physical symptoms such as pain and fatigue

- help with the emotional distress of dealing with a potential cancer diagnosis, anxiety/depression (particularly about potential loss of fertility), interpersonal problems, stress and adjustment difficulties

- referral to a fertility service for counselling and evaluation of options

- guidance about financial and employment issues (such as loss of income, travel and accommodation requirements for rural women and caring arrangements for other family members)

- appropriate information for women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Effective communication is essential at every step of the care pathway. Effective communication with the woman and her carer is particularly important given the prevalence of low health literacy in Australia (estimated at 60 per cent of Australian adults) (ACSQHC 2013).

The general or primary medical practitioner who made the referral is responsible for the woman until care is passed to another practitioner.

The general or primary medical practitioner may play a number of roles in all stages of the cancer pathway including diagnosis, referral, treatment, coordination and continuity of care as well as providing information and support to the woman and her family.

The general or primary practitioner should:

- provide the woman with information that clearly describes who they are being referred to, the reason for referral and the expected timeframe for appointments

- support the woman while waiting for the specialist appointment.

Cancer Council nurses are available to act as a point of information and reassurance during the anxiety-provoking period of awaiting further diagnostic information. Contact 13 11 20 nationally to speak to a cancer nurse. Health professionals can also access this service.

Step 3 outlines the process for confirming the diagnosis and stage of cancer, and planning subsequent treatment. The guiding principle is that interaction between appropriate multidisciplinary team members should determine the treatment plan.

All cervical cancer must be histologically confirmed. In the vast majority of cases this will occur as an outcome of the screening and subsequent investigation process. For women presenting with signs and symptoms suggesting the presence of cervical cancer, expedited colposcopy and histological evaluation is required.

After a thorough medical history and examination, the sequence of investigations depicted may be considered.

Investigations include:

- gynaecological examination

- colposcopic assessment prior to treatment by a practitioner certified in this field

- cervical biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis

- cone biopsy (conisation)/type 3 excision is recommended if the cervical biopsy is inadequate to define invasiveness or if accurate assessment of microinvasive disease is required) (NCCN 2017)

- complete blood count (including platelets), and liver and renal function tests (NCCN 2017)

- pelvic ultrasound (in cases where no lower genital tract abnormality is detected at colposcopy after referral with abnormal glandular cytology)

- endocervical sampling for suspected glandular abnormalities and HPV 16/18 positivity

- endometrial sampling to exclude an endometrial origin for atypical glandular cells (if required) (Cancer Council Australia 2016).

Timeframes for completing investigations should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce the woman’s distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Cervical Cancer Working Group:

- For obvious abnormalities, a colposcopy within two weeks of referral.

- Diagnostic investigations should be completed within two weeks of specialist review.

Staging is the cornerstone of treatment planning and prognosis. Staging for cervical cancer is clinical but aided by the following investigations as appropriate:

- chest x-ray

- CT/MRI/PET.

Structured reporting by a pathologist is encouraged (Royal College of Pathologists 2013; 2017).

All newly diagnosed women should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting so that a treatment plan can be recommended. The level of discussion may vary depending on both clinical and psychosocial factors.

The results of all relevant tests and imaging should be available for the multidisciplinary team discussion. Information about the woman’s concerns, preferences and social circumstances should also be available.

These are to:

- nominate a team member to be the lead clinician (the lead clinician may change over time depending on the stage of the care pathway and where care is being provided)

- nominate a team member to coordinate patient care

- develop and document an agreed treatment plan at the multidisciplinary team meeting

- circulate the agreed treatment plan to relevant team members, including the general practitioner.

The general or primary medical practitioner who made the referral is responsible for the patient until care is passed to another practitioner.

The general or primary medical practitioner may play a number of roles in all stages of the cancer pathway including diagnosis, referral, treatment, coordination and continuity of care as well as providing information and support to the woman and her family.

The care coordinator is responsible for ensuring there is continuity throughout the care process and coordination of all necessary care for a particular phase. The care coordinator may change over the course of the pathway.

The lead clinician is a clinician responsible for overseeing the activity of the team and for implementing treatment within the multidisciplinary setting.

The multidisciplinary team should comprise the core disciplines that are integral to providing good care. Team membership will vary according to cancer type but should reflect both the clinical and psychosocial aspects of care. Additional expertise or specialist services may be required for some women (Department of Health 2007b).

Team members may include a:

- care coordinator (as determined by multidisciplinary team members)*

- gynaecological oncologist*

- medical oncologist*

- nurse (with appropriate expertise)*

- pathologist with expertise in gynaecological pathology*

- radiation oncologist*

- radiologist*

- expert in providing culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer (this may be an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander health worker, health practitioner or hospital liaison officer)

- clinical trials coordinator

- dietitian

- fertility expert

- psychosexual counsellor

- women’s health physiotherapist

- general practitioner

- geriatrician

- gynaecologist

- occupational therapist

- palliative care specialist

- pharmacist

- physiotherapist

- psychologist

- psychiatrist

- social worker.

* Core members of the multidisciplinary team are expected to attend most multidisciplinary team meetings either in person or remotely.

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate. Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Special considerations that need to be addressed at this stage include issues regarding fertility, early menopause and changes to sexual function.

The risk of early-onset menopause continues after chemotherapy/radiotherapy and not only immediately following treatment. Referral for psychological services or a women’s health or sexual and reproductive health practitioner may be appropriate regarding changes to sexual function and loss of fertility, particularly for younger women.

The option of fertility preservation needs to be discussed prior to treatment starting. Referral to a fertility service for counselling and evaluation of options may be appropriate. Fertility-sparing

approaches may be considered in highly selected patients who have been thoroughly counselled regarding disease risk as well as prenatal and perinatal issues (NCCN 2017).

Referral to a social worker, women’s health physiotherapist, psychosexual counsellor, menopause expert, psychologist or psychiatrist may be appropriate.

Cancer prehabilitation uses a multidisciplinary approach combining exercise, nutrition and psychological strategies to prepare women for the challenges of cancer treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiation therapy.

Evidence indicates that for newly diagnosed cancer patients, prehabilitation prior to starting treatment can be beneficial. This may include conducting a physical and psychological assessment to establish a baseline function level, identifying impairments and providing targeted interventions to improve the woman’s health, thereby reducing the incidence and severity of current and future impairments related to cancer and its treatment (Silver & Baima 2013).

Medications should be reviewed at this point to ensure optimisation and to improve adherence to medicines used for comorbid conditions.

Screening with a validated screening tool (such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist) and assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals or organisations is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include:

- treatment for physical symptoms such as fatigue and pain

- malnutrition (as identified using a validated malnutrition screening tool or presenting with unintentional weight loss)

- help with psychological and emotional distress while adjusting to the diagnosis, treatment phobias, existential concerns, stress, difficulties making treatment decisions, anxiety/ depression, psychosexual issues such as potential loss of fertility and premature menopause, and interpersonal problems. Women diagnosed with cervical cancer may experience a unique emotional and psychological burden because it is largely a preventable cancer, as well as being associated with a sexually transmitted virus, raising the spectre of guilt and blame (Hobbs 2008)

- appropriate assistance for women with mental illness, women in residential care facilities, women in custodial care and women who are financially disadvantaged to access care

- guidance for financial and employment issues (such as loss of income, travel and accommodation requirements for rural women and caring arrangements for other family members)

- guidance for smoking cessation

- appropriate information for women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The lead clinician should:

- establish if the woman has a regular or preferred general practitioner

- discuss a timeframe for diagnosis and treatment with the woman and her carer

- discuss issues regarding fertility and early menopause

- discuss the benefits of multidisciplinary care and make her aware that her health information will be available to the team for discussion at the multidisciplinary team meeting

- offer individualised cervical cancer information that meets the needs of the woman and her carer (this may involve advice from health professionals as well as written and visual resources)

- offer advice on how to access information and support from websites and community and national cancer services and support groups (for example, Cancer Council)

- use a professionally trained interpreter when communicating with women from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds (NICE 2004)

- if the woman is a smoker, provide information about smoking cessation.

The lead clinician should:

- ensure regular and timely (within a week) communication with the woman’s general practitioner regarding the treatment plan and recommendations from multidisciplinary team meetings and should notify the general practitioner if the woman does not attend appointments

- gather information from the general practitioner, including their perspective on the woman (psychological issues, social issues and comorbidities) and locally available support services

- contribute to the development of a chronic disease and mental healthcare plan as required

- discuss shared care arrangements, where appropriate

- invite the general practitioner to participate in multidisciplinary team meetings (consider using video or teleconferencing).

Step 4 outlines the treatment options for cervical cancer.

The intent of treatment can be defined as one of the following:

- curative

- anti-cancer therapy to improve quality of life and/or longevity without expectation of cure

- symptom palliation.

The morbidity and risks of treatment need to be balanced against the potential benefits.

The lead clinician should discuss treatment intent and prognosis with the woman and carer before beginning treatment.

If appropriate, advance care planning should be initiated with the woman at this stage because there can be multiple benefits such as ensuring her preferences are known and respected after the loss of decision-making capacity (AHMAC 2011).

Depending on the stage of the disease, primary treatment consists of surgery, radiotherapy or a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. For situations involving fertility, pregnancy and immunocompromised women (such as those with HIV) refer to section 4.3.

Where possible, sequential multimodality treatment should be avoided.

The advantages and disadvantages of each treatment and associated potential side effects should be discussed with the woman.

Surgery is typically reserved for women who have small tumours found only within the cervix (early-stage disease and smaller lesions) (NCCN 2017).

For women with early-stage disease who do not require fertility-sparing approaches, cone biopsy, simple/extrafascial hysterectomy and radical hysterectomy are options. Radical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node assessment is the preferred treatment approach. Removal of the ovaries should be individualised according to disease indications.

In selected cases surgery for fertility preservation may be possible.

The training and experience required of the surgeon are as follows:

- Gynaecological oncologist (FRANZCOG) with adequate training and experience in gynaecological cancer surgery and institutional cross-credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004).

Hospital or treatment unit characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- appropriate nursing and theatre resources to manage complex surgery

- 24-hour medical staff availability

- 24-hour operating room access

- specialist pathology

- in-house access to radiology

- an intensive care unit.

Concurrent chemoradiation is generally the primary treatment of choice for managing women with cervical cancer either as a definitive treatment for those with locally advanced disease or for those who are poor surgical candidates (NCCN 2017).

Definitive radiation therapy should consist of pelvic external beam radiation (EBRT) and intracavitary brachytherapy (ESMO Guidelines Working Group 2012) to be completed within 56 days. Concurrent radiosensitising chemotherapy with radiotherapy has been shown to significantly improve patient survival compared with radiotherapy alone (NCCN 2017).

In women with high-risk disease (lymph node metastases, parametrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, thickness of the residual muscular layer, tumour depth and tumour growth pattern) (Shinohara et al. 2004) postoperative radiation therapy plus/minus chemotherapy following surgery should be offered (ESMO Guidelines Working Group 2012). Where possible, patients with high-risk features who are likely to require adjuvant therapy following surgery should be identified upfront and considered for definitive chemoradiation to minimise the toxicities of trimodality treatment.

For women who present with distant metastatic disease, EBRT may be considered to control pelvic disease and other symptoms.

Training and experience of the radiation oncologist:

- Radiation oncologist (FRANZCR or equivalent) with adequate training and experience that enables institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004) and who is also a core member of a gynaecological oncology multidisciplinary team.

Hospital or treatment unit characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- trained radiotherapy nurses, physicists and therapists

- access to CT/MRI scanning for simulation and planning

- mechanisms for coordinating combined therapy (chemotherapy and radiation therapy), especially where the facility is not collocated

- access to allied health, especially nutrition health and advice.

There is evidence to suggest that higher caseloads have better clinical outcomes for patients treated with brachytherapy (Moon-Sing et al. 2014). Centres that do not have sufficient caseloads should establish processes to routinely refer brachytherapy cases to a high-volume centre.

Chemotherapy may be used as part of primary chemoradiation or adjuvant chemoradiation. It may also be used as neoadjuvant treatment in patients who have metastatic disease outside of the pelvis.

For women who present with distant metastatic or recurrent disease, primary treatment is often chemotherapy plus/ or minus biological therapy.

Training, experience and treatment centre characteristics

The following training and experience is required of the appropriate specialist(s):

- Medical oncologists (RACP or equivalent) must have adequate training and experience with institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004).

- Nurses must have adequate training in chemotherapy administration and handling and disposal of cytotoxic waste.

- Chemotherapy should be prepared by a pharmacist with adequate training in chemotherapy medication, including dosing calculations according to protocols, formulations and/or preparation.

- In a setting where no medical oncologist is locally available, some components of less complex therapies may be delivered by a medical practitioner and/or nurse with training and experience with credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area under the guidance of a medical oncologist. This should be in accordance with a detailed treatment plan or agreed protocol, and with communication as agreed with the medical oncologist or as clinically required.

Hospital or treatment unit characteristics for providing safe and quality care include:

- a clearly defined path to emergency care and advice after hours

- access to basic haematology and biochemistry testing

- cytotoxic drugs prepared in a pharmacy with appropriate facilities

- occupational health and safety guidelines regarding handling of cytotoxic drugs, including safe prescribing, preparation, dispensing, supplying, administering, storing, manufacturing, compounding and monitoring the effects of medicines (ACSQHC 2011)

- guidelines and protocols to deliver treatment safely (including dealing with extravasation of drugs).

Timeframes for surgery should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce the woman’s distress.

The following recommended timeframes are based on expert advice from the Cervical Cancer Working Group:

- Treatment should begin within four weeks of the decision to treat.

For women wishing to preserve their fertility, early cervical cancer (cancers that are small and confined to the cervix) can be managed conservatively, with cone biopsy or trachelectomy in selected cases (ESMO Guidelines Working Group 2012).

After childbearing is complete, hysterectomy can be considered for women who have had either radical trachelectomy or a cone biopsy for early-stage disease if they have chronic, persistent HPV infection, they have persistent abnormal cervical tests, or they desire this surgery (NCCN 2017).

For premenopausal women undergoing radiation therapy, consideration for ovarian transposition should be individualised (Gubbala et al. 2014; Mossa et al. 2015; Shou et al. 2015).

When diagnosed in pregnancy, management of cervical cancer will depend on the gestation at diagnosis and the stage of the cancer. In early pregnancy (before 24 weeks) termination of

pregnancy to facilitate cancer treatment may be recommended. After 24 weeks it may be possible to delay treatment until viability of the baby (around 34 weeks).

In a woman known to be HIV positive, cervical cancer is an AIDS-defining illness, and management in conjunction with infectious diseases experts is recommended (Maiman et al. 1997).

Ongoing assessment of the effects of treatment-related menopause is required.

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer and, in some cases, may be associated with survival benefits (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014). Communication about the value of palliative care in improving symptom management and quality of life and should be emphasised to women and their carers.

The multidisciplinary team should ensure women receive timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral should be based on need rather than prognosis.

Ensure the needs and preferences of the person’s family and carers are assessed and directly inform support and guidance about their role (Palliative Care Australia 2018).

The woman and her carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate. Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

The lead clinician should broach the woman’s use (or intended use) of complementary or alternative therapies not prescribed by the multidisciplinary team to discuss safety and efficacy and identify any potential toxicity or drug interactions.

The lead clinician should seek a comprehensive list of all complementary and alternative medicines being taken and explore the woman’s reason for using these therapies and the evidence base.

Most alternative therapies and some complementary therapies have not been assessed for efficacy or safety. Some have been studied and found to be harmful or ineffective.

Some complementary therapies may assist in some cases, and the treating team should be open to discussing the potential benefits for the individual.

If the woman expresses an interest in using complementary therapies, the lead clinician should consider referring them to health professionals within the multidisciplinary team who have knowledge of complementary and alternative therapies (such as a clinical pharmacist, dietitian or psychologist) to help her reach an informed decision.

The lead clinician should assure women who use complementary or alternative therapies that they can still access multidisciplinary team reviews (NBCC & NCCI 2003) and encourage full disclosure about therapies being used (Cancer Australia 2010).

Further information

Screening with a validated screening tool, assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals and/or organisations is required to meet the needs of individual women, their families and carers.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific issues that may arise include:

- treatment-related side effects including loss of fertility, sexual dysfunction and menopause, which require sensitive discussion and possible referral to a clinician skilled in this area

- maintaining vaginal health, managing dryness, bleeding, stenosis, dyspareunia, atrophic vaginitis, fistulas and pain as well as prevention of treatment-induced vaginal stenosis through early referral to a specialist nurse or women’s health physiotherapist for advice

- comorbidities where treatment for depression is required

- coping with hair loss (refer to Look Good, Feel Better; see ’Resource List’)

- malnutrition risk as identified by a validated malnutrition screening tool or unintentional weight loss of greater than five per cent of usual body weight

- lower limb lymphoedema and lymphadenectomy, a common treatment side effect in women with gynaecological cancers (NBCC & NCCI 2003) that can restrict mobility (referral to a lymphoedema clinic or lymphoedema specialist may be needed)

- physical symptoms such as pain and fatigue

- bladder or bowel dysfunction, gastrointestinal or abdominal symptoms, which may need monitoring and assessment

- decline in mobility and/or functional status as a result of treatment (a referral to physiotherapist, occupational therapist or exercise physiologist may be needed)

- assistance with managing complex medication regimens, multiple medications, assessment of side effects and assistance with difficulties swallowing medications (referral to a pharmacist may be required)

- emotional and psychological issues such as body image concerns, fatigue, existential anxiety, treatment phobias, anxiety/depression, relationship or interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns and disclosure of past history of sexual abuse or trauma

- potential isolation from normal support networks, particularly for rural women who are staying away from home for treatment

- financial issues related to loss of income and additional expenses as a result of illness and/or treatment

- legal issues including advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney or enduring guardian, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability

- the need for appropriate information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women or women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

The lead clinician should:

- discuss the treatment plan with the woman and carer, including the intent of treatment and expected outcomes, and provide a written plan

- provide the woman and carer with information on the possible side effects of treatment, self-management strategies and emergency contacts

- initiate a discussion regarding advance care planning with the woman and carer.

The lead clinician should:

- discuss with the general practitioner their role in symptom management, psychosocial care and referral to local services

- ensure regular and timely two-way communication regarding:

- the treatment plan, including intent and potential side effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the woman’s prognosis and their understanding of this

- enrolment in research and/or clinical trials

- changes in treatment or medications

- recommendations from the multidisciplinary team.

The transition from active treatment to post-treatment care is critical to long-term health. After completing their initial treatment, women should be provided with a treatment summary and follow- up care plan including a comprehensive list of issues identified by all members of the multidisciplinary team. Transition from acute to primary or community care will vary depending on the type and stage of cancer and needs to be planned. In some cases, women will require ongoing, hospital-based care.

In the past two decades the number of women surviving cancer has increased. International research shows there is an important need to focus on helping cancer survivors cope with life beyond their acute treatment. Cancer survivors experience particular issues, often different from women having active treatment for cancer.

Many cancer survivors experience persisting side effects at the end of treatment. Emotional and psychological issues include distress, anxiety, depression, cognitive changes and fear of cancer recurrence. Late effects may occur months or years later and are dependent on the type of cancer treatment. Survivors may experience altered relationships and may encounter practical issues, including difficulties with return to work or study, and financial hardship.

Survivors generally need to see a doctor for regular followup, often for five or more years after cancer treatment finishes. The Institute of Medicine, in its report From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition, describes four essential components of survivorship care (Hewitt et al. 2006):

- the prevention of recurrent and new cancers, as well as late effects

- surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence or second cancers, and screening and assessment for medical and psychosocial late effects

- interventions to deal with the consequences of cancer and cancer treatments (including management of symptoms, distress and practical issues)

- coordination of care between all providers to ensure the woman’s needs are met.

All women should be educated in managing their own health needs (NCSI 2015). If the woman is a smoker, provide information about smoking cessation.

After initial treatment, the woman, the woman’s nominated carer (as appropriate) and general practitioner should receive a treatment summary outlining:

- the diagnostic tests performed and results

- tumour characteristics

- the type and date of treatment(s)

- interventions and treatment plans from other health professionals

- supportive care services provided

- contact information for key care providers.

Responsibility for follow-up care should be agreed between the lead clinician, the general practitioner, relevant members of the multidisciplinary team and the woman, with an agreed plan documented that outlines:

- what medical follow-up is required (surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence or secondary cancers, screening and assessment for medical and psychosocial effects)

- care plans from other health professionals to manage the consequences of cancer and treatment

- a process for rapid re-entry to specialist medical services for suspected recurrence.

No definitive agreement exists on the best post-treatment follow-up. The options for follow-up should be discussed at the completion of the primary treatment. Some women will decide that the psychological trauma of follow-up is too unsettling and opt to attend follow-up visits only if they have symptoms. Some women may opt out of specialist follow-up. Others will be keen for surveillance, even though some may experience anxiety prior to the follow-up visits.

The following recommendations are based on expert advice from the Cervical Cancer Working Group:

- Clinical review including vaginal examination should take place.

- Vaginal vault cytology* and imaging should be performed as clinically indicated with an annual co-test (HPV and cytology). For example: three-monthly for the first two years, six-monthly in the

- third and fourth year, with a final review at five years. Thereafter, all women should have an annual co-test with a general practitioner.

- CT, MRI or PET/CT scan should be performed as clinically indicated (ESMO Guidelines Working Group 2012).

- Access to a range of health professionals may be required, including providing an end-of-treatment care plan.

Special circumstances

Following fertility preserving surgery:

- In year 1 of follow-up, a colposcopy is recommended every three months. Cytology and HPV testing (co-test) at 12 months.

- In year 2 and 3 of follow-up, a six-monthly colposcopy is recommended. An annual co-test is recommended for all women.

- In year 4 and 5 of follow-up, an annual colposcopy is recommended. An annual co-test is recommended for all women.

- Women should be advised to consider a hysterectomy when fertility is no longer required.

Following primary chemoradiation treatment:

- *Cytology should be avoided following treatment unless clinically indicated because of the high rate of false-positive results.

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate. Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Treatment-related loss of fertility and menopause (NBCC & NCCI 2003) requires sensitive discussion. The risk of early-onset menopause continues after chemotherapy and radiotherapy and not only immediately following treatment.

Women considering pregnancy after fertility-sparing treatment should have pre-pregnancy counselling and a formal cervical length assessment, which may require management before attempting pregnancy.

Ongoing assessment and management of (including hormonal therapy) for treatment-related menopause is required. Symptoms associated with treatment-induced menopause include night sweats, hot flushes, reduced libido and those related to reduced bone density. Symptoms, particularly vasomotor, may be more severe compared with women who go through natural menopause.

Radiation-induced vaginal toxicity (such as vaginal shortening and dyspareunia) can have a significant impact on sexual quality of life in these patients.

The lead clinician should provide the woman and carer with information about managing menopausal symptoms and other long-term side effects post chemoradiotherapy, including the use of hormonal therapy.

Referral to a social worker, menopause expert, fertility specialist, psychosexual counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist may be appropriate, especially for younger women.

Screening using a validated screening tool, assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals and community-based support services is required to meet the needs of individual women, their families and carers.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific issues that may arise include:

- treatment-related side effects including loss of fertility, sexual dysfunction and menopause, which require sensitive discussion and possible referral to a clinician skilled in this area

- maintaining vaginal health, managing dryness, bleeding, stenosis, dyspareunia, atrophic vaginitis, fistulas and pain as well as prevention of treatment-induced vaginal stenosis through early referral to a specialist nurse or women’s health physiotherapist for advice

- comorbidities where treatment for depression is required

- coping with hair loss (refer to Look Good, Feel Better; see ’Resource List’)

- malnutrition risk as identified by a validated malnutrition screening tool or unintentional weight loss of greater than five per cent of usual body weight

- lower limb lymphoedema and lymphadenectomy, a common treatment side effect in women with gynaecological cancers (NBCC & NCCI 2003) that can restrict mobility (referral to a

- physiotherapist or trained lymphoedema massage specialist may be needed) (Beesley et al. 2007)

- physical symptoms including pain and fatigue

- bladder or bowel dysfunction, gastrointestinal or abdominal symptoms, which may need monitoring and assessment

- bowel obstruction due to malignancy (women need to be alerted to possible symptoms and advised to seek immediate medical assessment)

- decline in mobility and/or functional status as a result of treatment (a referral to physiotherapy and occupational therapy may be needed)

- emotional distress arising from fear of disease recurrence, changes in body image, returning to work, anxiety/depression, relationship or interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns

- potential isolation from normal support networks, particularly for rural women who are staying away from home for treatment

- abdominal ascites (abdominal symptoms need monitoring and assessment)

- cognitive changes as a result of treatment (such as altered memory, attention and concentration)

- financial and employment issues (such as loss of income and assistance with returning to work, and cost of treatment, travel and accommodation)

- legal issues including advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney or enduring guardian, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability

- the need for appropriate information for women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Rehabilitation may be required at any point of the care pathway from preparing for treatment through to disease-free survival and palliative care.

Issues that may need to be addressed include managing cancer-related fatigue, cognitive changes, improving physical endurance, achieving independence in daily tasks, returning to work and ongoing adjustment to disease and its sequelae.

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer and, in some cases, may be associated with survival benefits (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014).

The lead clinician should ensure timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral to palliative care services should be based on need, not prognosis.

Patients should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Ensure the needs and preferences of the person’s family and carers are assessed and directly inform support and guidance about their role (Palliative Care Australia 2018).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

The lead clinician should:

- discuss the management of any of the issues identified in section 5.5.1)

- explain the treatment summary and follow-up care plan

- provide information about the signs and symptoms of recurrent disease

- provide information about secondary prevention and healthy living

- provide clear information about the role and benefits of palliative care.

The lead clinician should ensure regular, timely, two-way communication with the woman’s general practitioner regarding:

- the follow-up care plan

- potential late effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the woman’s progress

- recommendations from the multidisciplinary team

- any shared care arrangements

- a process for rapid re-entry to medical services for women with suspected recurrence.

Step 6 is concerned with managing recurrent or residual local and metastatic disease.

Patients with metastatic or recurrent cervical cancer are commonly symptomatic. Some cases of recurrent disease will be detected by routine follow-up in a woman who is asymptomatic.

There should be timely referral to the original multidisciplinary team (where possible), with referral to a specialist centre for recurrent disease as appropriate.

Treatment will depend on the location and extent of the recurrence and on previous management and the woman’s preferences.

Patients with a localised recurrence after initial treatment may be candidates for further treatment; options include radiation therapy and chemotherapy, or radical, including exenterative, surgery (NCCN 2017).

For most patients with distant metastases, an appropriate approach is chemotherapy plus/minus biological agents and/or palliative radiotherapy or best supportive care (NCCN 2017). The role of chemotherapy in such patients is palliative, with the primary objective to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life (ESMO Guidelines Working Group 2012).

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer and, in some cases, may be associated with survival benefits (Haines 2011; Temel et al. 2010; Zimmermann et al. 2014).

The lead clinician should ensure timely and appropriate referral to palliative care services. Referral to palliative care services should be based on need, not prognosis.

Women should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Ensure the needs and preferences of the person’s family and carers are assessed and directly inform support and guidance about their role (Palliative Care Australia 2018).

Begin discussions with the woman and her carer about her preferred place of death.

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate. Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Screening, assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals is required to meet the identified needs of an individual, their carer and family.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific issues that may arise include:

- emotional and psychological distress resulting from fear of death/dying, existential concerns, anticipatory grief, communicating wishes to loved ones, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns including disclosure of past history of sexual abuse or trauma

- increased practical and emotional support needs for families and carers, including help with family communication, teamwork and care coordination where these prove difficult for families

- loss of fertility, sexual dysfunction or other symptoms associated with treatment-induced or related menopause, which requires sensitive discussion and possible referral to a clinician skilled in this area

- coping with hair loss and changes in physical appearance (refer to Look Good, Feel Better;

- see ’Resource List’)

- malnutrition risk as identified by a validated malnutrition screening tool or unintentional weight loss of greater than five per cent of usual body weight

- lower limb lymphoedema, a common treatment side effect in women with gynaecological cancers (NBCC & NCCI 2003) that can restrict mobility (referral to a lymphoedema clinic, physiotherapist or trained lymphoedema specialist may be needed) (Beesley et al. 2007)

- physical symptoms including pain and fatigue

- bladder or bowel dysfunction and gastrointestinal or abdominal symptoms, which may need monitoring and assessment

- urinary tract obstruction and renal failure

- bowel obstruction due to malignancy (women need to be alerted to possible symptoms and advised to seek immediate medical assessment)

- abdominal ascites (abdominal symptoms need monitoring and assessment)

- maintaining vaginal health, managing dryness, bleeding, stenosis, dyspareunia, atrophic vaginitis, fistulas and pain as well as prevention of treatment-induced vaginal stenosis through early referral to a specialist nurse or women’s health physiotherapist for advice

- decline in mobility and/or functional status as a result of recurrent disease and treatments (a referral to physiotherapy and occupational therapy may be needed)

- cognitive changes as a result of treatment (such as altered memory, attention and concentration)

- financial and employment issues (such as loss of income and assistance with returning to work, and cost of treatment, travel and accommodation)

- legal issues including advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney or enduring guardian, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability

- the need for appropriate information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Rehabilitation may be required at any point of the care pathway from preparing for treatment through to disease-free survival and palliative care. Issues that may need to be addressed include managing cancer-related fatigue, cognitive changes, improving physical endurance, achieving independence in daily tasks, returning to work and ongoing adjustment to disease and its sequelae.

The lead clinician should ensure there is adequate discussion with the woman and her carer about the diagnosis and recommended treatment, including the intent of treatment and possible outcomes, likely adverse effects and supportive care options available.

End-of-life care is appropriate when the woman’s symptoms are increasing and functional status is declining. Step 7 is concerned with maintaining the woman’s quality of life and addressing her health and supportive care needs as she approaches the end of life, as well as the needs of her family and carer. Consideration of appropriate venues of care is essential. The principles of a palliative approach to care need to be shared by the team when making decisions with the woman and her family.

If not already involved, referral to palliative care should be considered at this stage (including nursing, pastoral care, palliative medicine specialist backup, inpatient palliative bed access as required, social work and bereavement counselling), with general practitioner engagement.

If not already in place, the patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

The multidisciplinary palliative care team may consider seeking additional expertise from a:

- pain service

- pastoral carer or spiritual advisor

- bereavement counsellor

- therapist (for example, music or art).

The team might also recommend accessing:

- home- and community-based care

- specialist community palliative care workers

- community nursing.

Consideration of appropriate place of care and preferred place of death is essential.

Ensure the needs and preferences of the person’s family and carers are assessed and directly inform support and guidance about their role (Palliative Care Australia 2018).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

Participation in research and clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate. Cross-referral between clinical trials centres should be encouraged to facilitate participation.

For more information visit Australian Cancer Trials.

Screening, assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals is required to meet the identified needs of the woman, her carer and family.

In addition to the common issues identified in the Appendix, specific issues that may arise at this time include:

- emotional and psychological distress from anticipatory grief, fear of death/dying, anxiety/ depression, interpersonal problems and anticipatory bereavement support for the woman as well as her carer and family

- practical, financial and emotional impacts on carers and family members resulting from the increased care needs of the woman

- legal issues including advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney or enduring guardian, completing a will and making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability

- arranging a funeral (provide information to the woman and her family)

- specific spiritual needs that may benefit from the involvement of pastoral care

- bereavement support for family and friends

- specific support for families where a parent is dying and will leave behind bereaved children or adolescents, creating special family needs

- physical symptoms including pain and fatigue

- change in physical appearance

- increasing dependence on others

- bowel obstruction or small bowel dysfunction (bowel issues such as constipation, diarrhoea and cramps may require support from a dietitian, continence nurse, stomal therapist or medical specialist)

- abdominal ascites (abdominal symptoms need monitoring and assessment)

- decline in mobility and/or functional status impacting on the woman’s discharge destination (a referral to physiotherapy and occupational therapy may be needed).

The lead clinician should:

- be open to and encourage discussion about the expected disease course, with due consideration to personal and cultural beliefs and expectations

- discuss palliative care options including inpatient and community-based services as well as dying at home and subsequent arrangements

- provide the woman and her carer with the contact details of a palliative care service.

The lead clinician should discuss end-of-life care planning and transition planning to ensure the woman’s needs and goals are addressed in the appropriate environment. The woman’s general practitioner should be kept fully informed and involved in major developments in the woman’s illness trajectory.

Planning and delivering appropriate cancer care for older women presents a number of challenges. Improved communication between the fields of oncology and geriatrics is required to facilitate the delivery of best practice care, which takes into account physiological age, complex comorbidities, risk of adverse events and drug interactions, as well as the implications of cognitive impairment on suitability of treatment and consent (Steer et al. 2009).

A national interdisciplinary workshop convened by the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia recommended that women over the age of 70 undergo some form of geriatric assessment, in line with international guidelines (COSA 2013). This assessment can be used to determine life expectancy and treatment tolerance as well as identifying conditions that might interfere with treatment including:

- function

- comorbidity

- presence of geriatric syndromes

- nutrition

- polypharmacy

- cognition

- emotional status

- social supports.

Guided intervention using aged care services is appropriate.

Recent years have seen the emergence of adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology as a distinct field due to lack of progress in survival and quality-of-life outcomes (Ferrari et al. 2010; NCI & USDHHS 2006; Smith et al. 2013). The significant developmental change that occurs during this life stage complicates a diagnosis of cancer during the AYA years, often leading to unique physical, social and emotional impacts for young women at the time of diagnosis and throughout the cancer journey (Smith et al. 2012).

In caring for young women with cancer, careful attention to the promotion of normal development is required (COSA 2011). This requires personalised assessments and management involving a multidisciplinary, disease-specific, developmentally targeted approach informed by:

- understanding the developmental stages of adolescence and supporting normal adolescent health and development alongside cancer management

- understanding and supporting the rights of young women

- communication skills and information delivery that are appropriate to the young woman

- addressing the needs of all involved, including the young woman, her family and/or carer(s)

- working with educational institutions and workplaces

- addressing survivorship and palliative care needs.

An oncology team caring for a young woman with cancer must:

- ensure access to expert AYA health professionals who have specific knowledge about the biomedical and psychosocial needs of the population

- understand the biology and current management of the disease in the AYA age group

- consider clinical trials accessibility and recruitment for each woman

- engage in proactive discussions about fertility preservation and the late effects of treatment and consider the woman’s psychosocial needs

- provide treatment in an AYA-friendly environment.

Youth cancer services are available in each state/territory and can provide further advice and resources. See the resource list for contact information.

The burden of cancer is higher in the Australian Indigenous population (AIHW 2014), with cervical cancer occurring more frequently than among non-Indigenous people (AIHW 2017).

Survival also significantly decreases as remoteness increases, unlike the survival rates of non- Indigenous Australians. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia have high rates of certain lifestyle risk factors including tobacco smoking, higher alcohol consumption, poor diet and low levels of physical activity (Cancer Australia 2013). The high prevalence of these risk factors is believed to be a significant contributing factor to the patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates in this population group (Robotin et al. 2008).

In caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people diagnosed with cancer, the current gap in survivorship is a significant issue. The following approaches are recommended to improve survivorship outcomes (Cancer Australia 2013):

- Raise awareness of risk factors and deliver key cancer messages.

- Develop evidence-based information and resources for community and health professionals.

- Provide training for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers and develop training resources.

- Increase understanding of barriers to care and support.

- Encourage and fund research.

- Improve knowledge within the community to act on cancer risk and symptoms.