Breast cancer

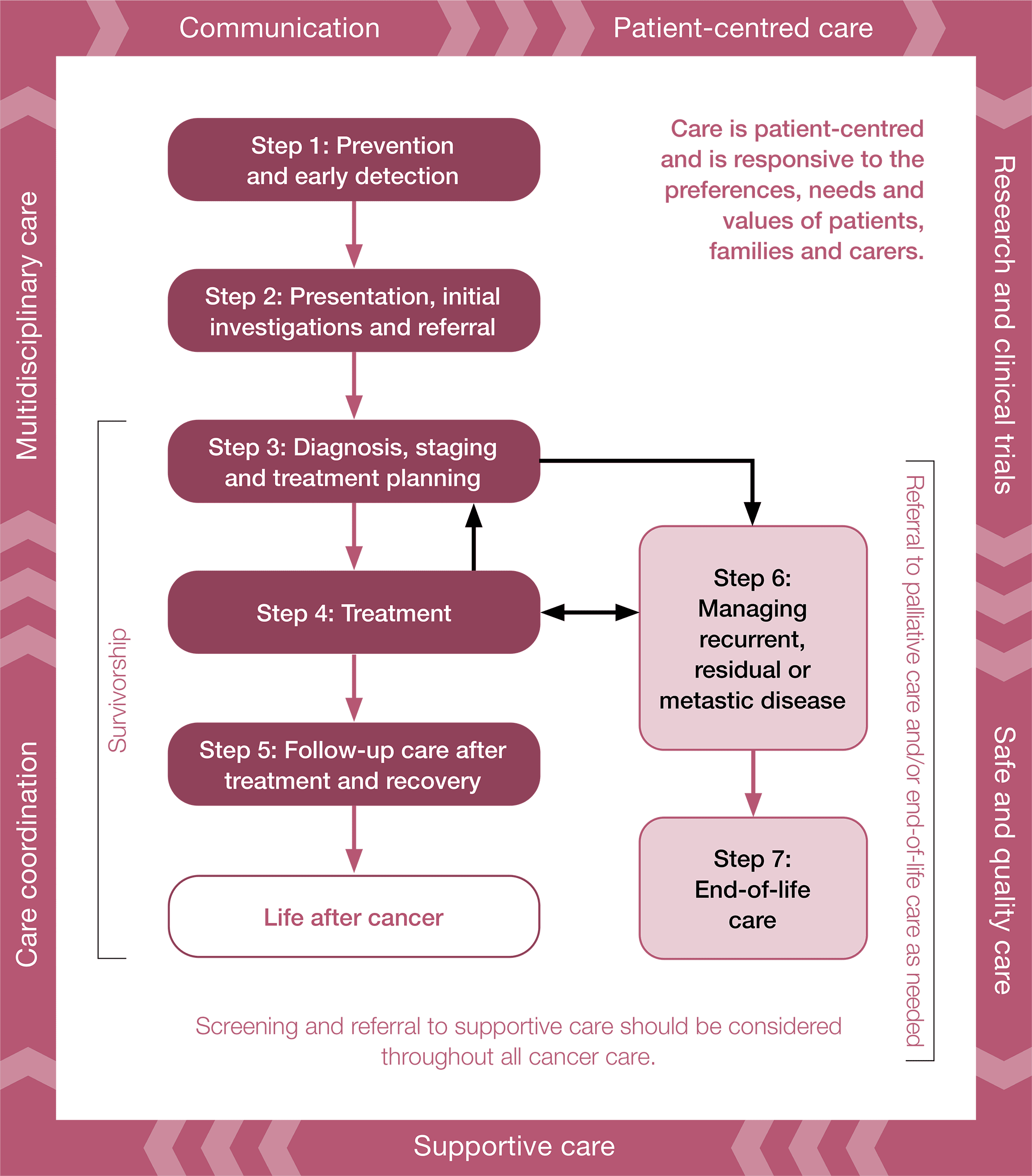

Optimal care pathways map seven key steps in cancer care. Each of these steps outlines nationally agreed best practice for the best level of care. While the seven steps appear in a linear model, in practice, patient care does not always occur in this way but depends on the particular situation (e.g. the type of cancer, when and how the cancer is diagnosed, prognosis, management, the patient’s decisions and their physiological response to treatment).

The principles underpinning optimal care pathways always put patients at the centre of care throughout their experience and prompt the healthcare system to deliver coordinated care.

The optimal care pathways do not constitute medical advice or replace clinical judgement, and they refer to clinical guidelines and other resources where appropriate.

Evidence-based guidelines, where they exist, should inform timeframes. Treatment teams need to recognise that shorter timeframes for appropriate consultations and treatment often promote a better experience for patients. Three steps in the pathway specify timeframes for care. They are designed to help patients understand the timeframes in which they can expect to be assessed and treated, and to help health services plan care delivery in accordance with expert-informed time parameters to meet the expectation of patients. These timeframes are based on expert advice from the Breast Cancer Working Group, recognising that they may not always be possible.

Timeframes for care

|

Step in pathway |

Care point |

Timeframe |

|

Presentation, initial investigations and referral |

Signs and symptoms |

A patient with signs and symptoms that may suggest breast cancer should be seen by a GP within 2 weeks |

|

Initial investigations initiated by GP |

Optimally, tests should be done within 2 weeks |

|

|

Referral to specialist |

A positive result on any component of the triple test warrants specialist surgical referral. Ideally the surgeon should see the patient with proven or suspected cancer within 2 weeks of diagnosis. If necessary, prior discussion should facilitate referral |

|

|

Diagnosis, staging and treatment planning |

Diagnosis and staging |

Diagnostic investigations should be completed within 2 weeks of the initial specialist consultation |

|

Multidisciplinary meeting and treatment planning |

Ideally, the multidisciplinary team should discuss all newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer prior to surgery or neoadjuvant chemotherapy Results of all relevant tests and imaging should be available for the MDM Referral to a breast cancer nurse within 7 days of definitive diagnosis |

|

|

Treatment |

Surgery |

Surgery should occur ideally within 5 weeks of the decision to treat (for invasive breast cancer) |

|

Chemotherapy and Systemic therapy |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy should begin within 4 weeks of the decision to treat Adjuvant chemotherapy should begin within 6 weeks of surgery Adjuvant chemotherapy for triple-negative breast and HER2-positive breast cancer should begin within 4 weeks of surgery Endocrine therapy should begin as soon as appropriate after completing chemotherapy, radiation therapy and/or surgery (and in some cases will be started in the neoadjuvant setting) |

|

|

Radiation therapy |

For patients who don’t have adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy should begin within 8 weeks of surgery For patients who have adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy should begin 3–4 weeks after chemotherapy |

Seven steps of the optimal care pathway

Step 1: Prevention and early detection

Step 2: Presentation, initial investigations and referral of patients with suspected breast cancer

Step 3: Diagnosis, staging and treatment planning

Step 4: Treatment

Step 5: Care after initial treatment and recovery

Step 6: Managing recurrent, residual or metastatic disease

Step 7: End-of-life care

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in Australian women, accounting for more than 29 per cent of newly diagnosed cancers. It is second only to lung cancer as the most common cause of death from cancer (AIHW 2019).

Breast cancer in men accounts for less than 1 per cent of all breast cancers, with 90 per cent of men diagnosed with breast cancer after the age of 50 (Cancer Australia 2016). The recommendations in this document apply to all patients unless otherwise specified.

Early breast cancer may or may not have spread to lymph nodes in the armpit. Advanced breast cancer comprises both locally advanced breast and metastatic breast cancer (Cardoso et al. 2018). Locally advanced breast cancer is breast cancer with extensive axillary nodal involvement and that may have spread to areas near the breast, such as the chest wall.

This step outlines recommendations for the prevention and early detection of breast cancer.

Evidence shows that not smoking, avoiding or limiting alcohol intake, eating a healthy diet, maintaining a healthy body weight, being physically active, being sun smart and avoiding exposure to oncoviruses or carcinogens may help reduce most cancer risk (Cancer Council Australia 2018).

These are the convincing risk factors for developing breast cancer (Cancer Australia 2018) (those highlighted in bold are modifiable):

- age

- gender (being female)

- significant family history of breast cancer and/or other cancers

- pathogenic variants in cancer predisposition genes including BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, PALB2, PTEN, NF1, STK11, TP53, ATM and CHEK2

- DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ)

- LCIS (lobular carcinoma in situ) also referred to as non-invasive lobular neoplasia

- atypical epithelial proliferative lesions (atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia)

- previous breast cancer

- high mammographic breast density (must be adjusted for age and body mass index)

- early menarche

- not bearing children

- never having breastfed

- late age at first birth

- late menopause

- maternal exposure to diethylstilboestrol (DES) in utero

- use of combined hormone replacement therapy, particularly for extended periods over many years

- not engaging in adequate physically active

- overweight and obesity (only for postmenopausal women)

- weight gain (postmenopausal)

- alcohol consumption

- exposure of the breast to ionising radiation.

For more information, visit the Cancer Australia breast cancer risk factor website.

Recommendations that may assist in preventing breast cancer include:

- maintaining a healthy weight

- avoiding or limiting alcohol intake to no more than 10 standard drinks a week and no more than four standard drinks on any one day

- getting 30 minutes or more of moderate-intensity (puffing) exercise most days (150–300 minutes per week)

- avoiding or limiting hormone replacement therapy use

- additional prevention strategies in people with increased risk (e.g. gene mutation carriers).

Additional prevention interventions are considered for women at increased risk, including those at moderately increased risk. For example, those at moderately increased risk (1.5–3 times the population risk) may be offered medication to reduce risk, and those at high risk (more than three times the population risk) may be offered medication or risk-reducing surgery.

Everyone should be encouraged to reduce their modifiable risk factors (see section 1.1).

For women assessed as having an increased risk of breast cancer, antihormonal risk-reducing medication such as tamoxifen, raloxifene or an aromatase inhibitor is an option to lower the risk of developing breast cancer. Decisions about whether to use risk-reducing medication should be based on an accurate risk assessment and clear understanding of the absolute benefits and risks for each individual woman. The benefits and risks for an individual can be assessed by using iPrevent.

Risk-reducing surgery such as prophylactic bilateral mastectomy may be considered by women at high risk of developing breast cancer (NCI 2015), including those with a mutation in a major breast cancer predisposition gene such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 (Cancer Council Australia 2015).

Bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy reduces the absolute risk of breast cancer by at least 90 per cent (NCI 2015). Even with total mastectomy, not all breast tissue can be removed. The remaining breast tissue may be at risk of becoming cancerous in the future (NCI 2013).

Knowledge of a woman’s risk factors can be used to objectively assess her individual breast cancer risk using a validated tool such as iPrevent.

By accurately assessing a woman’s personal breast cancer risk level, health professionals can offer the most appropriate evidence-based prevention and early detection strategies. All women should therefore consider having their individual breast cancer risk assessed. This can be done by women themselves or in primary care. Cancer risk assessment should be repeated when major risk factors change (e.g. new family cancer history, breast biopsy showing atypical hyperplasia or LCIS).

There are a number of validated computerised breast cancer risk assessment tools that estimate a woman’s breast cancer risk based on her individual risk factors:

iPrevent is an Australian tool designed for self-administration by women and collaborative use with clinicians and is the only tool that links the risk assessment directly to the relevant risk management guidelines.

In Australia, absolute lifetime population risk of breast cancer is 12 per cent, but most women are below this risk. Cancer Australia defines levels of breast cancer risk as follows:

- average risk: < 1.5 × population risk

- moderate risk: 1.5–3 × population risk

- high risk: > 3 × population risk (Cancer Australia 2010).

People with or without a personal history of breast cancer at high risk due to their family cancer history should be referred to a familial cancer service for further risk assessment and for possible genetic testing (eviQ 2019a). Consider referring:

- untested adult blood relatives of a person with a known pathogenic variant (mutation) in a breast and/or ovarian cancer predisposition gene (e.g. BRCA1 or BRCA2, TP53, PTEN, STK11, PALB2, CDH1, NF1) or

- people with two first- or second-degree relatives diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer plus one or more of the following on the same side of the family:

- additional relative(s) with breast or ovarian cancer

- breast cancer diagnosed under age 50 years

- more than one primary breast cancer in the same woman

- breast and ovarian cancer in the same woman

- Jewish ancestry

- breast cancer in a male

- pancreatic cancer

- high-grade (≥ Gleason 7) prostate cancer.

Additionally, people with breast cancer should be referred to a familial cancer service if they meet the following criteria:

- male breast cancer at any age

- breast cancer and Jewish ancestry

- two primary breast cancers in the same person, where the first occurred under age 60 years

- two or more different but associated cancers in the same person at any age (e.g. breast and ovarian cancer)

- breast cancer aged under 40 years or triple-negative breast cancer aged under 50 years

- lobular breast cancer and a family history of lobular breast or diffuse-type gastric cancer

- breast cancer aged under 50 years with limited family structure or knowledge (e.g. adopted)

- breast cancer and a personal or family history suggestive of:

- Peutz-Jegher syndrome (oral pigmentation and/or gastrointestinal polyposis)

- PTEN hamartoma syndrome (macrocephaly, specific mucocutaneous lesions, endometrial or thyroid cancer)

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (breast cancer < 50 years, adrenocorticocarcinoma, sarcoma, brain tumours).

Referral can also be considered if finding a relevant germline mutation would have high clinical utility (e.g. would alter treatment of the current cancer).

Asymptomatic women

A significant proportion of breast cancers are diagnosed through mammographic screening in women who are asymptomatic. Assess a woman’s individualised risk to see whether a personalised screening regimen may be appropriate.

Early detection through screening mammography has several benefits including improved mortality rates, increased treatment options and improved quality of life (Cancer Australia 2015a). For women with small tumours at diagnosis (< 10 mm), there is a more than 95 per cent five-year survival rate (Cancer Australia 2012).

BreastScreen Australia services operate within the framework of a comprehensive set of national accreditation standards that specify requirements for the safety and quality of diagnostic tests, timeliness of services and multidisciplinary care.

State, territory and federally funded two-yearly mammographic screening is offered to asymptomatic women from the age of 50 to 74 years through the BreastScreen Australia program (although available after 40 years of age upon request).

A doctor’s referral is not required for screening through BreastScreen Australia, but general practitioners’ encouragement is a key factor in women’s participation in screening.

Not all breast cancers are detectable on screening mammograms, and new cancers may arise in the interval between mammograms. Women should be aware of the look and feel of their breasts and report concerns to their general practitioner.

Women invited to screening should be provided with information about the risk and benefits of mammographic screening.

There is a 42 per cent reduction in risk of dying from breast cancer in screened women (AIHW 2018b) and a significant reduction in treatment intensity for patients diagnosed within a screening program.

Screening can lead to anxiety, additional investigations for non-malignant processes, over-diagnosis and treatment of cancers that may never have needed treatment. Over-diagnosis could occur due to lesions that may not progress to invasive cancer during the woman’s lifetime. Some lesions that need investigation based on their imaging features turn out not to be cancer. Providing women with information on risks and benefits can assist them to make informed decisions around screening participation (Cancer Australia 2014).

For more information, see Cancer Australia’s position statement on over-diagnosis.

If a woman is reported as having high mammographic density please refer to the IBIS risk tool.

Symptomatic people

People who have symptoms or signs of breast cancer require prompt investigation of their symptoms, including diagnostic imaging. Screening mammography is not recommended for these people because it may lead to false reassurance and delayed diagnosis.

This step outlines the process for the general practitioner to initiate the right investigations and refer to the appropriate specialist in a timely manner. The types of investigations the general practitioner undertakes will depend on many factors, including access to diagnostic tests, the availability of medical specialists and patient preferences.

At least one-third of breast cancers are found in apparently asymptomatic women through routine breast cancer screening, and participation in BreastScreen Australia should be encouraged for eligible women. The remaining women have symptomatic presentations.

The following signs and symptoms should be investigated:

- a persistent new lump or lumpiness, especially involving only one breast

- a change in the size or shape of a breast

- a change to a nipple, such as crusting, ulceration, redness or inversion

- a nipple discharge that occurs without manual expression

- a change in the skin of a breast such as redness, thickening or dimpling

- axillary mass(es)

- an unusual breast pain that does not go away (Cancer Australia 2020b; Walker et al 2014).

People with symptoms as described above should not attend BreastScreen because they will require diagnostic imaging either publicly or privately.

A patient with signs and symptoms that may suggest breast cancer should be seen by a general practitioner within two weeks.

The types of investigation undertaken by a general practitioner depend on many factors including access to diagnostic tests and medical specialists and the patient’s preferences. General practitioners should refer all patients with a suspicious sign or symptom to a breast assessment clinic.

General practitioner examinations and investigations should include a triple test of three diagnostic components:

- medical history and clinical breast examination

- imaging – mammography and/or ultrasound

- non-excision biopsy – preferably core biopsy (Cancer Australia 2017a; Farshid et al. 2019). Pathologists should expedite such testing as part of routine clinical care. Funding through the Medicare Benefits Schedule is accessible for receptor profile evaluation of screen-detected cancers, including immunohistochemistry for ER, PR and HER2 and, when necessary, in situ hybridisation to assess HER2 gene amplification.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy does not permit distinction between invasive cancer and in situ malignancy. Evaluation of grade and subtype are not reliable, and cytology is inappropriate for assessing a cancer’s receptor profile (ER, PR, HER2), critical for optimal treatment planning, including suitability of neoadjuvant therapy. Fine-needle aspiration cytology may be considered if the clinical and imaging features suggest a benign process, particularly a cystic lesion. If cytology results are non-diagnostic, atypical, suspicious or malignant, core biopsy is needed.

Based on the best available evidence, the triple test provides the most effective means of excluding breast cancer in patients with breast symptoms. A positive result on any component of the triple test warrants referral for specialist surgical assessment and/or further investigation, irrespective of any other normal test results. This implies that not all three components of the triple test need to be performed to reach the conclusion that appropriate referral is needed. The triple test is positive if any component is indeterminate, suspicious or malignant (Cancer Australia 2017a).

For screen-detected lesions, a 2020 review by Cancer Australia established that core biopsy (including vacuum-assisted core biopsy) is the procedure of choice for assessing most screen-detected breast abnormalities (Cancer Australia 2020c). Fine-needle aspiration in the screening setting is appropriate for simple cysts, some complex cystic lesions, axillary lymph nodes and rare situations where a core biopsy is hazardous or technically difficult.

BreastScreen Australia services take responsibility for screening and investigation of screen-detected lesions, including needle biopsies. After multidisciplinary assessment and review of results, recommendations are made for the next steps in management. The woman and her general practitioner are advised of these recommendations in writing. Surgery and ongoing care are typically not part of the BreastScreen program and must be coordinated by the general practitioner through appropriate surgical referral.

To enable timely treatment planning, including consideration of neoadjuvant therapies, it is preferable that the histologic findings, including the receptor profile results, be available in time for the patient’s first consultation with the treating surgeon. Information could be provided to patients to enable them to make an informed decision on neoadjuvant therapy. See Breast Cancer Trials ‘Neoadjuvant patient decision aid’ brochure.

Optimally, tests should be done within two weeks.

Any patient with symptoms suspicious of breast cancer can be referred for specialist assessment as first line. If the diagnosis of breast malignancy is confirmed or the results are inconsistent or indeterminate, referral to a BreastSurgANZ member breast surgeon is warranted. See BreastSurgANZ ‘Find a surgeon’ for a directory.

Patients should be enabled to make informed decisions about their choice of specialist and health service. General practitioners should make referrals in consultation with the patient after considering the clinical care needed, cost implications (see referral options and informed financial consent), waiting periods, location and facilities, including discussing the patient’s preference for health care through the public or the private system.

Referral for suspected or diagnosed breast cancer should include the following essential information to accurately triage and categorise the level of clinical urgency:

- important psychosocial history and relevant medical history

- family history, current symptoms, medications and allergies

- results of current clinical investigations (imaging and pathology reports with ER, PR and HER2 receptor profile)

- results of all prior relevant investigations

- notification if an interpreter service is required.

Many services will reject incomplete referrals, so it is important that referrals comply with all relevant health service criteria.

If access is via online referral, a lack of a hard copy should not delay referral.

The specialist should provide timely communication to the general practitioner about the consultation and should notify the general practitioner if the patient does not attend appointments.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients will need a culturally appropriate referral. To view the optimal care pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the corresponding quick reference guide, visit the Cancer Australia website. Download the consumer resources – Checking for cancer and Cancer from the Cancer Australia website.

A positive result on any component of the triple test warrants specialist surgical referral. Ideally, the surgeon should see the patient with proven or suspected cancer within two weeks of diagnosis. If necessary, prior discussion should facilitate referral.

The patient’s general practitioner should consider an individualised supportive care assessment where appropriate to identify the needs of an individual, their carer and family. Refer to appropriate support services as required. See validated screening tools mentioned in Principle 4 ‘Supportive care’.

A number of specific needs may arise for patients at this time:

- assistance for dealing with the emotional distress and/or anger of dealing with a potential cancer diagnosis, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems and adjustment difficulties

- access to expert health professionals with specific knowledge about the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients

- encouragement and support to increase levels of exercise (Cormie et al. 2018; Hayes et al. 2019).

For more information refer to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2015 guidelines, Suspected cancer: recognition and referral.

For additional information on supportive care and needs that may arise for different population groups, see Appendices A and B, and special population groups.

The general practitioner is responsible for:

- providing patients with information that clearly describes to whom they are being referred, the reason for referral and the expected timeframes for appointments

- outlining their potential role and that of the primary care team throughout treatment and follow-up care (Cancer Australia 2020d)

- considering referral to a breast care nurse such as a McGrath breast care nurse or a nurse in a local breast cancer centre

- considering referral to Breast Cancer Network Australia’s ‘My Journey online tool’ and local community-based support such as peer support

- requesting that patients notify them if the specialist has not been in contact within the expected timeframe

- considering referral options for patients living rurally or remotely

supporting the patient while waiting for the specialist appointment (Cancer Council nurses are available to act as a point of information and reassurance during the anxious period of awaiting further diagnostic information; patients can contact 13 11 20 nationally to speak to a cancer nurse).

Refer to Principle 6 ‘Communication’ for communication skills training programs and resources.

Step 3 outlines the process for confirming the diagnosis and stage of cancer and for planning subsequent treatment. The guiding principle is that interaction between appropriate multidisciplinary team members should determine the treatment plan.

The treatment team, after taking a medical history and making a medical examination of the patient, should undertake the following investigations under the guidance of a specialist:

- appropriate breast imaging tests including bilateral mammography and ultrasound (if conventional imaging is insufficient to help guide treatment, consider MRI)

- ultrasound of the axilla (including fine-needle aspiration of nodes if the axillary ultrasound is abnormal)

- breast core biopsy, if not already undertaken (which allows determination of breast cancer receptor profiles [ER, PR, HER2]).

Patients should be assessed for the possibility of a breast cancer predisposition gene and considered for genetic counselling/testing if appropriate. For more information refer to eviQ’s Referral guidelines for breast cancer risk assessment and consideration of genetic testing.

Diagnostic investigations should be completed within two weeks of the initial specialist consultation.

People with breast cancer should be referred for genetic work-up early in their treatment journey if they fulfil germline testing criteria using CanRisk or the Manchester score, or have a triple-negative breast cancer under 50 years of age. Other factors pertaining to genetic work-up include a personal or family history suggestive of:

- Peutz-Jegher syndrome (oral pigmentation and/or gastrointestinal polyposis)

- PTEN hamartoma syndrome (macrocephaly, specific mucocutaneous lesions, endometrial or thyroid cancer)

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (breast cancer < 50 years, adrenocorticocarcinoma, sarcoma, brain tumours).

Family history-based testing threshold can be assessed using the Manchester score APP.

In some cases certain pathological subtypes of cancer or tumour tests (immunohistochemistry or tumour genetic tests) may suggest an underlying inherited cancer predisposition, especially triple-negative breast cancers.

Genetic testing is sometimes able to identify the cause of cancer in a family and may be used to guide treatment for the affected people.

A familial cancer service assessment can determine if genetic testing is appropriate. Genetic testing is likely to be offered when there is at least a 10 per cent chance of finding a causative ‘gene error’ (pathogenic gene variant; previously called a mutation). Usually testing begins with a variant search in a person who has had cancer (a diagnostic genetic test). If a pathogenic gene variant is identified, variant-specific testing is available to relatives to see if they have or have not inherited the familial gene variant (predictive genetic testing).

Medicare funds some genetic tests via a Medicare Benefits Schedule item number. Depending on the personal and family history, the relevant state health system may fund public sector genetic testing.

Pre-test counselling and informed consent is required before any genetic testing. In some states the treating team can offer ‘mainstream’ diagnostic genetic testing, after which referral is made to a familial cancer service if a pathogenic gene variant is identified. The familial cancer service can provide risk management advice, facilitate family risk notification and arrange predictive genetic testing for the family.

Visit the Centre for Genetics Education website for basic information about cancer in a family.

For detailed information and referral guidelines for breast cancer risk assessment and consideration of genetic testing, read eviQ’s Referral guidelines for breast cancer risk assessment and consideration of genetic testing.

Routine staging with, for example, computed tomography (CT) and bone scan are not recommended for most patients with early breast cancer. For a patient presenting with de novo metastatic disease, see Step 6.

Staging is appropriate for patients with confirmed locally advanced or nodal disease and for any patient with clinical symptoms or clinical suspicion of metastatic disease. PET scan may be the most appropriate modality.

Visit the Cancer Institute New South Wales website for information about understanding the stages of cancer.

Patient performance status is a central factor in cancer care and should be clearly documented in the patient’s medical record.

Performance status should be measured and recorded using an established scale such as the Karnofsky scale or the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale.

People over the age of 70 years should undergo some form of geriatric assessment (COSA 2013; palliAGED 2018). Screening tools can be used to identify those patients in need of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (Decoster et al. 2015). This assessment can be used to help determine life expectancy and treatment tolerance and guide appropriate referral for multidisciplinary intervention that may improve outcomes (Wildiers et al. 2014).

A number of factors should be considered at this stage:

- the patient’s overall condition, life expectancy, decision-making capacity and results from a geriatric assessment if appropriate in those over the age of 70 years

- patient preferences and aims of treatment

- psychosocial screening/evaluation and support

- discussing the multidisciplinary team approach to care with the patient

- ensuring a breast care nurse is part of the multidisciplinary team

- appropriate and timely referral to an MDM

- considering if an interpreter is required

- pregnancy and fertility options, contraception and prevention of chemotherapy-induced menopause

- financial and social aspects

- support with travel and accommodation

- teleconferencing or videoconferencing as required.

Discussion at an MDM is a core component of quality care (ASCO & ESMO 2006). All patients with a new diagnosis of breast cancer should be referred to an MDM for discussion. Ideally, the multidisciplinary team should discuss all newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer prior to surgery or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Results of all relevant tests and imaging should be available for the MDM. To assist with the burden of demand, sites may streamline and prioritise the MDM discussion using agreed protocols. Patients should be offered a referral to a breast cancer nurse within seven days of a definitive diagnosis.

Patients may be discussed at several time points during their diagnosis and treatment. This can ensure patients are identified who may benefit from neoadjuvant systemic therapy, where surgical decisions are complex and in planning of reconstructive surgery and sequencing of therapies, or for relevant clinical trials.

The multidisciplinary team requires administrative support in developing the agenda for the meeting, for collating patient information and to ensure appropriate expertise around the table to create an effective treatment plan for the patient. The MDM has a chair and multiple lead clinicians. Each patient case will be presented by a lead clinician (usually someone who has seen the patient before the MDM). In public hospital settings, the registrar or clinical fellow may take this role. A member of the team records the outcomes of the discussion and treatment plan in the patient history and ensures these details are communicated to the patient’s general practitioner.

When developing treatment recommendations for each patient, MDM participants ensure:

- the tumour has been adequately staged

- all appropriate treatment modalities are considered

- psychosocial and medical comorbidities that may influence treatment decisions are considered

- the patient’s treatment preferences are known and considered

- clinical trial eligibility, availability and participation are considered

- relevant optimal care pathway timeframes are considered.

The team should consider the patient’s values, beliefs and cultural needs as appropriate to ensure the treatment plan is in line with these. There may be early consideration of post-treatment pathways at this point – for example, shared follow-up care.

MDMs should aim to develop and agree by consensus an individualised treatment plan for each patient discussed. At times when there is a divergence of opinion about a patient’s management or equivalent options, these differing opinions should be discussed with the patient to enable them to make an informed decision. Patients should be given time to discuss treatment options with others before making this decision.

MDM recommendations should be communicated in a timely manner to the patient and referring doctor/general practitioner with formal documentation. Further details regarding MDM requirements can be found via the Victorian cancer multidisciplinary team meeting quality framework.

The multidisciplinary team should be composed of the core disciplines that are integral to providing good care. Team membership should reflect both clinical and supportive care aspects of care. Pathology and radiology expertise are essential.

See ‘About this OCP’ for a list of team members who may be included in the multidisciplinary team for breast cancer.

Core members of the multidisciplinary team are expected to attend most MDMs either in person or remotely via virtual mechanisms. Additional expertise or specialist services may be required for some patients such as breast cancer patients during pregnancy. An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural expert should be considered for all patients who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

The general practitioner who made the referral is responsible for the patient until care is passed to another practitioner who is directly involved in planning the patient’s care.

The general practitioner may play a number of roles in all stages of the cancer pathway including diagnosis, referral, treatment, shared follow-up care, post-treatment surveillance, coordination and continuity of care, as well as managing existing health issues and providing information and support to the patient, their family and carer.

A nominated contact person from the multidisciplinary team may be assigned responsibility for coordinating care in this phase. Care coordinators (usually a breast care nurse) are responsible for ensuring there is continuity throughout the care process and coordination of all necessary care for a particular phase (COSA 2015). The care coordinator may change over the course of the pathway.

The lead clinician is responsible for overseeing the activity of the team and for implementing treatment within the multidisciplinary setting.

Patients should be encouraged to participate in research or clinical trials where available and appropriate.

For more information visit:

Cancer prehabilitation uses a multidisciplinary approach combining exercise, nutrition and psychological strategies to prepare patients for the challenges of cancer treatment such as surgery, systemic therapy and radiation therapy. Team members may include anaesthetists, oncologists, surgeons, haematologists, clinical psychologists, exercise physiologists, physiotherapists and dietitians, among others.

Patient performance status is a central factor in cancer care and should be frequently assessed. All patients should be screened for malnutrition using a validated tool, such as the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST). The lead clinician may refer obese or malnourished patients to a dietitian preoperatively or before other treatments begin.

Patients who currently smoke should be encouraged to stop smoking before receiving treatment. This should include an offer of referral to Quitline in addition to smoking cessation pharmacotherapy if clinically appropriate.

Evidence indicates that patients who respond well to prehabilitation may have fewer complications after treatment. For example, those who were exercising before diagnosis and patients who use prehabilitation before starting treatment may improve their physical or psychological outcomes, or both, and this helps patients to function at a higher level throughout their cancer treatment (Cormie et al. 2017; Silver 2015).

A key contact person, ideally a breast care nurse, should be agreed as soon as possible (within seven days is optimal) to support communication and coordination of patient-centred care. Consultations may be via telephone and/or videoconferencing, where appropriate (Cancer Australia 2020e).

For patients with breast cancer, the multidisciplinary team should consider these specific prehabilitation assessments and interventions for treatment-related complications or major side effects:

- conducting a physical and psychological assessment to establish a baseline function level

- identifying impairments and providing targeted interventions to improve the patient’s function level (Silver & Baima 2013)

- reviewing the patient’s medication to ensure optimisation and to improve adherence to medicine used for comorbid conditions. Some medications, such as anticoagulants, may need to be modified before surgery.

Following completion of primary cancer treatment, rehabilitation programs have considerable potential to enhance physical function.

See Breast Cancer Network Australia’s ‘Physical Preparation & Recovery After Breast Reconstruction’.

Cancer and cancer treatment may cause fertility problems. This will depend on the age of the patient, the type of cancer and the treatment received. Infertility can range from difficulty having a child to the inability to have a child. Infertility after treatment may be temporary, lasting months to years, or permanent (AYA Cancer Fertility Preservation Guidance Working Group 2014).

Patients need to be advised about and potentially referred for discussion about fertility preservation before starting treatment and need advice about contraception before, during and after treatment. Patients and their family should be aware of the ongoing costs involved in optimising fertility. Fertility management may apply in both men and women. Fertility preservation options are different for men and women and the need for ongoing contraception applies to both men and women.

The potential for impaired fertility should be discussed and reinforced at different time points as appropriate throughout the diagnosis, treatment, surveillance and survivorship phases of care. These ongoing discussions will enable the patient and, if applicable, the family to make informed decisions. All discussions should be documented in the patient’s medical record.

See the Cancer Council website for more information.

See Breast Cancer Network Australia’s fertility video for more information.

See validated screening tools mentioned in Principle 4 ‘Supportive care’.

A number of specific challenges and needs may arise for patients at this time:

- assistance for dealing with psychological and emotional distress while adjusting to the diagnosis; treatment phobias; existential concerns; stress; difficulties making treatment decisions; anxiety or depression or both; psychosexual issues such as potential loss of fertility and premature menopause; history of sexual abuse; and interpersonal problems

- access to expert health professionals with specific knowledge about the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients

- for some populations (culturally diverse backgrounds, Aboriginal people and lesbian, transgender and intersex communities) a breast cancer diagnosis comes with additional psychosocial complexities, and discrimination uncertainty may also make these groups less inclined to seek regular medical care – access to expert health professionals with specific knowledge about the psychosocial needs of these groups may be required

- preservation of ovarian function should be discussed before starting treatment – goserelin reduces the risk of chemotherapy-induced menopause and should particularly be discussed before chemotherapy for women with ER-negative breast cancer (for some women with ER-positive breast cancer it may also be appropriate to use goserelin before and during chemotherapy; see Breast Cancer Network Australia’s Fertility-related choices booklet

- management of physical symptoms such as pain and fatigue (Australian Adult Cancer Pain Management Guideline Working Party 2019)

- upper limb and breast lymphoedema and cording following lymphadenectomy – this is a potential treatment side effect in people with breast cancer, which has a significant effect on survivor quality of life; referral (preferably preoperatively) to a health professional with accredited lymphoedema management qualifications, offering the full scope of complex lymphoedema therapy, should be encouraged

- limitations in upper limb movement and function, which may affect radiation therapy – referral to a physiotherapist may be required (prospective monitoring, particularly for high-risk patients is recommended)

- weight changes, which can be a significant issue for patients, and may require referral to a dietitian before, during and after treatment

- malnutrition or undernutrition, identified using a validated nutrition screening tool such as the MST (note that many patients with a high body mass index [obese patients] may also be malnourished [WHO 2018])

- support for families or carers who are distressed with the patient’s cancer diagnosis

- support for families/relatives who may be distressed after learning of a genetically linked cancer diagnosis

- specific spiritual needs that may benefit from the involvement of pastoral/spiritual care

- financial and employment issues (such as loss of income and having to deal with travel and accommodation requirements for rural patients and caring arrangements for other family members).

Additionally, palliative care may be required at this stage.

For more information on supportive care and needs that may arise for different population groups, see Appendices A and B, and special population groups.

In discussion with the patient, the lead clinician should undertake the following:

- establish if the patient has a regular or preferred general practitioner and if the patient does not have one, then encourage them to find one

- provide written information appropriate to the health literacy of the patient about the diagnosis and treatment to the patient and carer and refer the patient to the Guide to best cancer care (consumer optimal care pathway) for breast cancer, as well as to relevant websites and support groups as appropriate

- refer the patient to Breast Cancer Network Australia’s ‘My Journey online tool’

- discuss the importance of relatives accessing predictive genetic testing when a pathogenic variant is identified in the patient

- provide a treatment care plan including contact details for the treating team and information on when to call the hospital

- discuss a timeframe for diagnosis and treatment with the patient and carer

- discuss the benefits of multidisciplinary care and gain the patient’s consent before presenting their case at an MDM

- provide brief advice and refer to Quitline (13 7848) for behavioural intervention if the patient currently smokes (or has recently quit), and prescribe smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, if clinically appropriate

- recommend an ‘integrated approach’ throughout treatment regarding nutrition, exercise and minimal or no alcohol consumption among other considerations

- communicate the benefits of continued engagement with primary care during treatment for managing comorbid disease, health promotion, care coordination and holistic care

- where appropriate, review fertility needs with the patient and refer for specialist fertility management (including fertility preservation, contraception, management during pregnancy and of future pregnancies)

- be open to and encourage discussion about the diagnosis, prognosis (if the patient wishes to know) and survivorship and palliative care while clarifying the patient’s preferences and needs, personal and cultural beliefs and expectations, and their ability to comprehend the communication

- encourage the patient to participate in advance care planning including considering appointing one or more substitute decision-makers and completing an advance care directive to clearly document their treatment preferences. Each state and territory has different terminology and legislation surrounding advance care directives and substitute decision-makers.

Consider appointing one lead clinician at the time of initial diagnosis; however, all treating clinicians have these communication responsibilities:

- involving the general practitioner from the point of diagnosis

- ensuring regular and timely communication with the general practitioner about the diagnosis, treatment plan and recommendations from MDMs and inviting them to participate in MDMs (consider using virtual mechanisms)

- gathering information from the general practitioner including their perspective on the patient’s psychosocial issues and comorbidities and locally available support services

- supporting the role of general practice both during and after treatment

- discussing shared or team care arrangements with general practitioners or regional cancer specialists, or both, together with the patient

- contributing to the development of a chronic disease and mental health care plan as required, particularly to access community supportive care service

- notifying the general practitioner if the patient does not attend appointments.

Refer to Principle 6 ‘Communication’ for communication skills training programs and resources.

Step 4 describes the optimal treatments for breast cancer, the training and experience required of the treating clinicians and the health service characteristics required for optimal cancer care.

All health services must have clinical governance systems that meet the following integral requirements:

- identifying safety and quality measures

- monitoring and reporting on performance and outcomes

- identifying areas for improvement in safety and quality (ACSQHC 2020).

Step 4 outlines the treatment options for breast cancer. For detailed clinical information on treatment options refer to this resource:

The intent of treatment can be defined as one of the following:

- curative

- anti-cancer therapy to improve quality of life and/or longevity without expectation of cure

- symptom palliation.

The treatment intent should be established in a multidisciplinary setting, documented in the patient’s medical record and conveyed to the patient and carer as appropriate.

The potential benefits need to be balanced against the morbidity and risks of treatment.

The appropriate clinician should discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each treatment and associated potential side effects with the patient and their carer or family before treatment consent is obtained and begins so the patient can make an informed decision. Supportive care services should also be considered during this decision-making process. Patients should be asked about their use of (current or intended) complementary/alternative therapies (see Appendix D).

Timeframes for starting treatment should be informed by evidence-based guidelines where they exist. The treatment team should recognise that shorter timeframes for appropriate consultations and treatment often promote a better experience for patients.

Initiate advance care planning discussions with patients before treatment begins (this could include appointing a substitute decision-maker and completing an advance care directive). Formally involving a palliative care team/service may benefit any patient, so it is important to know and respect each person’s preference (AHMAC 2011).

The aim of treatment for breast cancer and the types of treatment recommended depend on the type, stage and location of the cancer and the patient’s age, health and preferences.

Early and locally advanced breast cancer is treated with curative intent.

Surgery for early breast cancer involves either breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy. Breast conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy is as effective as mastectomy for most patients with early breast cancer.

Patients with invasive breast cancer and a clinically and radiologically negative axilla should generally be offered sentinel node biopsy. Axillary treatment with surgery and/or radiation therapy should be considered for patients with nodal disease.

Oncoplastic breast surgery should be considered where appropriate to ensure the patient has the best possible outcome. Surgery may involve the breast surgeon and plastic surgeon working together because some reconstructions are very complex. It is important that patients are given enough time to consider their reconstructive options. This may require more than one appointment with the treating surgeon. It is the responsibility of the multidisciplinary team to ensure the patient is referred in a timely manner to allow for adequate planning of the surgery.

Breast reconstruction surgery

Mastectomy can be performed with or without immediate breast reconstruction. Patients should be fully informed of their options and offered the option of immediate or delayed reconstructive surgery if appropriate.

Timeframe for starting treatment

- Surgery should occur ideally within five weeks of the decision to treat (for invasive breast cancer).

- If being treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgery is deferred until four to six weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, ensuring blood counts have recovered.

Training and experience required of the surgeon

- Breast surgeon (FRACS or equivalent, including membership of BreastSurgANZ) with adequate training and experience in breast cancer surgery and institutional agreed scope of practice within this area

- Plastic surgeon with an interest and expertise in breast reconstructive surgery and who contributes to the Australia Breast Device Registry

Documented evidence of the surgeon’s training and experience, including their specific (sub-specialty) experience with breast cancer and procedures to be undertaken, should be available.

Health service characteristics

To provide safe and quality care for patients having surgery, health services should have access to:

- appropriate nursing and theatre resources to manage complex surgery

- a breast care nurse

- a multidisciplinary team

- critical care support

- 24-hour medical staff availability

- 24-hour operating room access and intensive care unit

- specialist pathology expertise

- diagnostic imaging

- in-house access to specialist radiology and nuclear medicine expertise.

If appropriate, goserelin for preventing chemo-induced menopause should begin at least one week prior to chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant therapy, usually chemotherapy, may be appropriate for an increasing number of breast cancers, which may include tumours where the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy may direct future therapy (e.g. triple-negative and HER2-positive cancers, locally advanced or inflammatory breast cancers as well as some larger operable breast cancers to down-stage tumours), either to make them operable or to allow breast-conserving therapy. The receptor profile of the breast cancer (ER, PR, HER2) assessed by pathologists on the core biopsy is essential in making decisions about the appropriateness and nature of neoadjuvant therapies.

For early breast cancers following surgery, a further discussion at the MDM will determine the appropriateness and type of systemic therapy. All patients with invasive cancer should be considered for systemic therapy.

Patients with LCIS and atypical hyperplasia should be considered for endocrine therapy (tamoxifen or anastrozole) to reduce future invasive breast cancer risk.

All patients with HER2-positive breast cancers (> 5 mm) should be considered for HER2-directed therapy. All patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer should be considered for antihormonal therapy. Endocrine therapy should be administered for five years and sometimes longer in higher risk cases.

A core biopsy is the recommended sample for evaluating receptor profile in breast cancer. The information about receptor profile should be made available to the treating teams including the pathologist evaluating the cancer resection specimen. This information helps to identify cases of discordance where further assessment is required and to reduce unnecessary repeat testing.

For patients who have not had a complete pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy, repeat assessment of receptor profile on the resected breast cancer tissue is required to plan ongoing treatment.

Adjuvant bisphosphonates improve survival and should be considered for selected patients being treated for breast cancer with curative intent.

Timeframes for starting treatment

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy should begin within four weeks of the decision to treat with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy should begin within six weeks of surgery.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy for triple-negative breast and HER2-positive breast cancer should begin within four weeks of surgery.

- Endocrine therapy should begin as soon as appropriate after completing chemotherapy, radiation therapy and/or surgery (and in some cases will begin in the neoadjuvant setting).

Training and experience required of the appropriate specialists

Medical oncologists must have training and experience of this standard:

- Fellow of the Royal Australian College of Physicians or Medical Oncology Group of Australia (or equivalent)

- adequate training and experience that enables institutional credentialing and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2015).

Cancer (chemotherapy) nurses should have accredited training in these areas:

- anti-cancer treatment administration

- specialised nursing care for patients undergoing cancer treatments, including side effects and symptom management

- the handling and disposal of cytotoxic waste (ACSQHC 2020).

Systemic therapy should be prepared by a pharmacist whose background includes this experience:

- adequate training in systemic therapy medication, including dosing calculations according to protocols, formulations and/or preparation.

In a setting where no medical oncologist is locally available (e.g. regional or remote areas), some components of less complex therapies may be delivered by a general practitioner or nurse with training and experience that enables credentialing and agreed scope of practice within this area. This should be in accordance with a detailed treatment plan or agreed protocol, and with communication as agreed with the medical oncologist or as clinically required.

The training and experience of the appropriate specialist should be documented.

Health service characteristics

To provide safe and quality care for patients having systemic therapy, health services should have these features:

- a clearly defined path to emergency care and advice after hours

- access to diagnostic pathology including basic haematology and biochemistry, and imaging

- cytotoxic drugs prepared in a pharmacy with appropriate facilities

- occupational health and safety guidelines regarding handling of cytotoxic drugs, including preparation, waste procedures and spill kits (eviQ 2019b)

- guidelines and protocols to deliver treatment safely (including dealing with extravasation of drugs)

- coordination for combined therapy with radiation therapy, especially where facilities are not co-located

- appropriate molecular pathology access.

Radiation therapy is used to treat early, locally advanced, recurrent and metastatic breast cancer in conjunction with surgery and/or systemic treatments, depending on patient and disease factors.

In most cases, radiation therapy is recommended for patients with early breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery.

Hypofractionated radiation therapy (a three- to four-week course) should be considered for most patients with early breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving therapy.

Radiation therapy following mastectomy should be considered for selected patients.

Partial breast irradiation (including intraoperative radiation therapy or linac-based) can be considered for selected patients with early breast cancer.

Discussion at an MDM is essential.

Timeframe for starting treatment

- For patients who do not have adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy should begin within eight weeks of surgery.

- For patients who have adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy should begin three to four weeks after chemotherapy.

Training and experience required of the appropriate specialists

Radiation oncologist (FRANZCR or equivalent) with adequate training and experience that enables institutional credentialing and agreed scope of practice within this area.

The training and experience of the radiation oncologist should be documented.

Health service unit characteristics

To provide safe and quality care for patients having radiation therapy, health services should have these features:

- linear accelerator (LINAC) capable of image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT)

- dedicated CT planning

- access to MRI and PET imaging

- automatic record-verify of all radiation treatments delivered

- a treatment planning system

- trained medical physicists, radiation therapists and nurses with radiation therapy experience

- coordination for combined therapy with systemic therapy, especially where facilities are not co-located

- participation in Australian Clinical Dosimetry Service audits

- an incident management system linked with a quality management system.

The team should support the patient to participate in research or clinical trials where available and appropriate. Many emerging treatments are only available on clinical trials that may require referral to certain trial centres.

For more information visit:

See validated screening tools mentioned in Principle 4 ‘Supportive care’.

Assess the patient’s response to all treatments using clinical outcome measures and patient-reported measures.

A number of specific challenges and needs may arise for patients at this time:

- assistance for dealing with emotional and psychological issues, including body image concerns, fatigue, quitting smoking, traumatic experiences, existential anxiety, treatment phobias, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns

- access to expert health professionals with specific knowledge about the psychosocial needs of breast cancer patients

- potential isolation from normal support networks, particularly for rural patients who are staying away from home for treatment

- alteration of cognitive functioning in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which requires strategies such as maintaining written notes or a diary and repetition of information

- loss of fertility, sexual dysfunction or other symptoms associated with treatment or surgically or chemically induced menopause, which requires sensitive discussion and possible referral to a clinician skilled in this area

- general healthcare issues (e.g. smoking cessation and sleep disturbance), which can be referred to a general practitioner

- decline in mobility or functional status as a result of treatment

- management of physical symptoms such as pain, arthralgia and fatigue

- early management for acute pain postoperatively to avoid chronic pain

- side effects of chemotherapy such as neuropathy, cardiac dysfunction, nausea and vomiting; managing these side effects is important for improving quality of life

- managing complex medication regimens, multiple medications, assessment of side effects and assistance with difficulties swallowing medications – referral to a pharmacist may be required

- menopause symptoms, which may require referral to a menopause clinic

- upper limb problems following surgery including decreased range of movement, which may delay radiation therapy – referral to a physiotherapist may be required

- upper limb and breast lymphoedema following lymphadenectomy/radiation therapy – this is a potential treatment side effect in patients with breast cancer that has a significant effect on survivor quality of life; referral (preferably preoperatively) to a health professional with accredited lymphoedema management qualifications, offering the full scope of complex lymphoedema therapy, should be encouraged (prospective monitoring, particularly for high-risk patients is recommended)

- disfigurement and scarring from appearance-altering treatment (and possible need for a prosthetic), which may require referral to a specialist psychologist, psychiatrist or social worker

- weight changes – this may require referral to a dietitian before, during and after treatment

- bowel dysfunction, gastrointestinal or abdominal symptoms as a result of treatment, which may require support from a dietitian

- coping with hair loss and changes in physical appearance (refer to the Look Good, Feel Better program; see ’Resource List’ and/or consider scalp cooling)

- assistance with beginning or resuming regular exercise with referral to an exercise physiologist or physiotherapist (COSA 2018; Hayes et al. 2019).

Early involvement of general practitioners may lead to improved cancer survivorship care following acute treatment. General practitioners can address many supportive care needs through good communication and clear guidance from the specialist team (Emery 2014).

Patients, carers and families may have these additional issues and needs:

- financial issues related to loss of income (through reduced capacity to work or loss of work) and additional expenses as a result of illness or treatment

- advance care planning, which may involve appointing a substitute decision-maker and completing an advance care directive

- legal issues (completing a will, care of dependent children) or making an insurance, superannuation or social security claim on the basis of terminal illness or permanent disability.

Cancer Council’s 13 11 20 information and support line can assist with information and referral to local support services.

Breast Cancer Network Australia’s helpline (1800 500 258) and website can assist with information and support services.

For more information on supportive care and needs that may arise for different population groups, see A and B, and special population groups.

Rehabilitation may be required at any point of the care pathway. If it is required before treatment, it is referred to as prehabilitation (see section 3.6.1).

All members of the multidisciplinary team have an important role in promoting rehabilitation. Team members may include occupational therapists, speech pathologists, dietitians, social workers, psychologists, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists and rehabilitation specialists.

To maximise the safety and therapeutic effect of exercise for people with cancer, all team members should recommend that people with cancer work towards achieving, and then maintaining, recommended levels of exercise and physical activity as per relevant guidelines. Exercise should be prescribed and delivered under the direction of an accredited exercise physiologist or physiotherapist with experience in cancer care (Vardy et al. 2019). The focus of intervention from these health professionals is tailoring evidence-based exercise recommendations to the individual patient’s needs and abilities, with a focus on the patient transitioning to ongoing self-managed exercise.

Other issues that may need to be dealt with include managing cancer-related fatigue, improving physical endurance, achieving independence in daily tasks, optimising nutritional intake, returning to work and ongoing adjustment to cancer and its sequels. Referrals to dietitians, psychosocial support, return-to-work programs and community support organisations can help in managing these issues.

The lead or nominated clinician should take responsibility for these important aspects of treatment:

- discussing treatment options with patients and carers, including the treatment intent and expected outcomes, and providing a written version of the plan and any referrals

- providing patients and carers with information about the possible side effects of treatment, managing symptoms between active treatments, how to access care, self-management strategies and emergency contacts

- encouraging patients to use question prompt lists and audio recordings, and to have a support person present to aid informed decision making

- offering advice to patients and carers on the benefits of and how to access support

- initiating a discussion about advance care planning and involving carers or family if the patient wishes.

The general practitioner plays an important role in coordinating care for patients, including helping to manage side effects and other comorbidities, and offering support when patients have questions or worries. For most patients, simultaneous care provided by their general practitioner is very important.

The lead clinician, in discussion with the patient’s general practitioner, should consider these points:

- the general practitioner’s role in symptom management, supportive care and referral to local services

- using a chronic disease management plan and mental health care management plan

- how to ensure regular and timely two-way communication about:

- the treatment plan, including intent and potential side effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the patient’s prognosis and their understanding of this

- enrolment in research or clinical trials

- changes in treatment or medications

- the presence of an advance care directive or appointment of a substitute decision-maker

- recommendations from the multidisciplinary team.

Refer to Principle 6 ‘Communication’ for communication skills training programs and resources.

The term ‘cancer survivor’ describes a person living with cancer, from the point of diagnosis until the end of life. Survivorship care in Australia has traditionally been provided to patients who have completed active treatment and are in the post-treatment phase. But there is now a shift to provide survivorship care and services from the point of diagnosis to improve cancer-related outcomes.

Cancer survivors may experience inferior quality of life and cancer-related symptoms for up to five years after their diagnosis (Jefford et al. 2017). Distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, obesity and sedentary lifestyle are common symptoms reported by cancer survivors (Vardy et al. 2019).

Due to an ageing population and improvements in treatments and supportive care, the number of people surviving cancer is increasing. International research shows there is an important need to focus on helping cancer survivors cope with life beyond their acute treatment. Cancer survivors often face issues that are different from those experienced during active treatment for cancer and may include a range of issues, as well as unmet needs that affect their quality of life (Lisy et al. 2019; Tan et al. 2019).

Physical, emotional and psychological issues include fear of cancer recurrence, cancer-related fatigue, pain, distress, anxiety, depression, cognitive changes and sleep issues (Lisy et al. 2019). Late effects may occur months or years later and depend on the type of cancer treatment. Survivors and their carers may experience impacted relationships and practical issues including difficulties with return to work or study and financial hardship. They may also experience changes to sex and intimacy. Fertility, contraception and pregnancy care after treatment may require specialist input.

The Institute of Medicine, in its report From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition, describes the essential components of survivorship care listed in the paragraph above, including interventions and surveillance mechanisms to manage the issues a cancer survivor may face (Hewitt et al. 2006). Access to a range of health professions may be required including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work, dietetics, clinical psychology, fertility and palliative care. Coordinating care between all providers is essential to ensure the patient’s needs are met.

Cancer survivors are more likely than the general population to have and/or develop comorbidities (Vijayvergia & Denlinger 2015). Health professionals should support survivors to self-manage their own health needs and to make informed decisions about lifestyle behaviours that promote wellness and improve their quality of life (Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre 2016; Cancer Australia 2017b; NCSI 2015).

Breast Cancer Network Australia provides information and support designed specifically for the transition to life after treatment.

The transition from active treatment to post-treatment care is critical to long-term health. In some cases, people will need ongoing, hospital-based care, and in other cases a shared follow-up care arrangement with their general practitioner may be appropriate. This will vary depending on the type and stage of cancer and needs to be planned.

Shared follow-up care involves the joint participation of specialists and general practitioners in the planned delivery of follow-up and survivorship care. A shared care plan is developed that outlines the responsibilities of members of the care team, the follow-up schedule, triggers for review, plans for rapid access into each setting and agreement regarding format, frequency and triggers for communication.

Shared follow-up care for early breast cancer is an innovative model of care that supports holistic follow-up and survivorship care following active treatment (Cancer Australia 2019c).

After completing initial treatment, a designated member of the multidisciplinary team (most commonly nursing or medical staff involved in the patient’s care) should provide the patient with a needs assessment and treatment summary and develop a survivorship care plan in conjunction with the patient. This should include a comprehensive list of issues identified by all members of the multidisciplinary team involved in the patient’s care and by the patient. These documents are key resources for the patient and their healthcare providers and can be used to improve communication and care coordination.

The treatment summary should cover, but is not limited to:

- the diagnostic tests performed and results

- diagnosis including stage, prognostic or severity score

- tumour characteristics

- treatment received (types and dates)

- current toxicities (severity, management and expected outcomes)

- interventions and treatment plans from other health providers

- potential long-term and late effects of treatment

- supportive care services provided

- follow-up schedule

- contact information for key healthcare providers.

Responsibility for follow-up care should be agreed between the lead clinician, the general practitioner, relevant members of the multidisciplinary team and the patient. This is based on guideline recommendations for post-treatment care, as well as the patient’s current and anticipated physical and emotional needs and preferences.

The options for follow-up should encompass the following:

- A follow-up schedule will be planned based on the patient’s individual circumstances.

- Investigations should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

- Most follow-up will involve a history, including updating personal history and enquiry about persistent symptoms that might require investigation to exclude metastatic disease. Family cancer history should be updated.

- If the patient has previously had genetic testing that revealed an unclassified variant in a cancer predisposition gene, the clinician should liaise regularly with the relevant familial cancer service until the variant is classified as benign or pathogenic.

- In the case of a pathogenic variant, the clinician should prompt predictive testing in close blood relatives and recommend referral to a familial cancer service.

- Physical examination, and particularly breast examination and limb circumference measure, should be conducted. Annual mammography (unless the patient underwent a bilateral mastectomy) should be undertaken. In some cases it may be appropriate to also undertake breast ultrasound or MRI.

- Appropriate follow-up does not involve chest x-rays, bone scans, CT scans, positron emission tomography (PET) scans or blood tests unless the cancer has spread or there are symptoms suggesting metastases.

- Toxicity related to treatment should be monitored and managed, including bone health

- and cardiovascular health (Blaes & Konety 2020). There is a significant role for physiotherapy in preventing osteoporosis.

- Premenopausal women who develop amenorrhoea are at risk of rapid bone loss. There is evidence that oral bisphosphonates are effective in reducing bone loss.

- Continue to prompt general good health.

Adherence to ongoing recommended treatment such as endocrine therapy should be reviewed and side effects managed proactively to optimise adherence.

Evidence comparing shared follow-up care and hospital-based care indicates equivalence in outcomes including recurrence rate, cancer survival and quality of life (Cancer Research in Primary Care 2016).

Ongoing communication between healthcare providers involved in care and a clear understanding of roles and responsibilities is key to effective survivorship care.

In particular circumstances, other models of post-treatment care can be safely and effectively provided such as nurse-led models of care (Monterosso et al. 2019). Other models of post-treatment care can be provided in these locations or by these health professionals:

- in a shared care setting

- in a general practice setting

- by non-medical staff

- by allied health or nurses

- in a non-face-to-face setting (e.g. by telehealth).

A designated member of the team should document the agreed survivorship care plan. The survivorship care plan should support wellness and have a strong emphasis on healthy lifestyle changes such as a balanced diet, a non-sedentary lifestyle, weight management and a mix of aerobic and resistance exercise (COSA 2018; Hayes et al. 2019).

This survivorship care plan should also cover, but is not limited to:

- what medical follow-up is required (surveillance for recurrence or secondary and metachronous cancers, screening and assessment for medical and psychosocial effects)

- model of post-treatment care, the health professional providing care and where it will be delivered

- care plans from other health providers to manage the consequences of cancer and cancer treatment

- wellbeing, primary and secondary prevention health recommendations that align with chronic disease management principles

- rehabilitation recommendations

- available support services

- a process for rapid re-entry to specialist medical services for suspected recurrence.

Survivors generally need regular follow-up, often for five or more years after cancer treatment finishes. The survivorship care plan therefore may need to be updated to reflect changes in the patient’s clinical and psychosocial status and needs.

Processes for rapid re-entry to hospital care should be documented and communicated to the patient and relevant stakeholders.

Care in the post-treatment phase is driven by predicted risks (e.g. the risk of recurrence, developing late effects of treatment and psychological issues) as well as individual clinical and supportive care needs. It is important that post-treatment care is based on evidence and is consistent with guidelines. Not all people will require ongoing tests or clinical review and may be discharged to general practice follow-up.

The lead clinician should discuss (and general practitioner reinforce) options for follow-up at the start and end of treatment. It is critical for optimal aftercare that the designated member of the treatment team educates the patient about the symptoms of recurrence.

General practitioners (including nurses) can:

- connect patients to local community services and programs

- manage long-term and late effects

- manage comorbidities

- provide wellbeing information and advice to promote self-management

- screen for cancer and non-cancerous conditions.

Templates and other resources to help with developing treatment summaries and survivorship care plans are available from these organisations:

- Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre

- Cancer Australia – Principles of Cancer Survivorship

- Cancer Australia – Shared cancer follow-up and survivorship care: early breast cancer

- Cancer Council Australia and states and territories

- Clinical Oncology Society of Australia – Model of Survivorship Care

- eviQ – Cancer survivorship: introductory course

- MyCarePlan.org.au

- South Australian Cancer Service – Statewide Survivorship Framework resources

- American Society of Clinical Oncology – guidelines.