STEP 4: Treatment

Step 4 provides an overview of the treatment options for CUP. For detailed information on treatment options refer to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

Refer also to the ESMO CUP guidelines.

The intent of treatment can be defined as one of the following:

- curative

- anti-cancer therapy to improve quality of life and/or longevity without expectation of cure, or

- symptom palliation.

The morbidity and risks of treatment need to be balanced against the potential benefits. The advantages and disadvantages of each treatment and associated potential side effects should be discussed with the patient.

The lead clinician should discuss treatment intent and prognosis with the patient and their family/ carer before beginning treatment.

Advance care planning should be initiated with patients and their carers as there can be multiple benefits such as ensuring a person’s preferences are known and respected after the loss of decision-making capacity (AHMAC 2011).

The advantages and disadvantages of each treatment and associated potential side effects should be discussed with the patient and their carer/family.

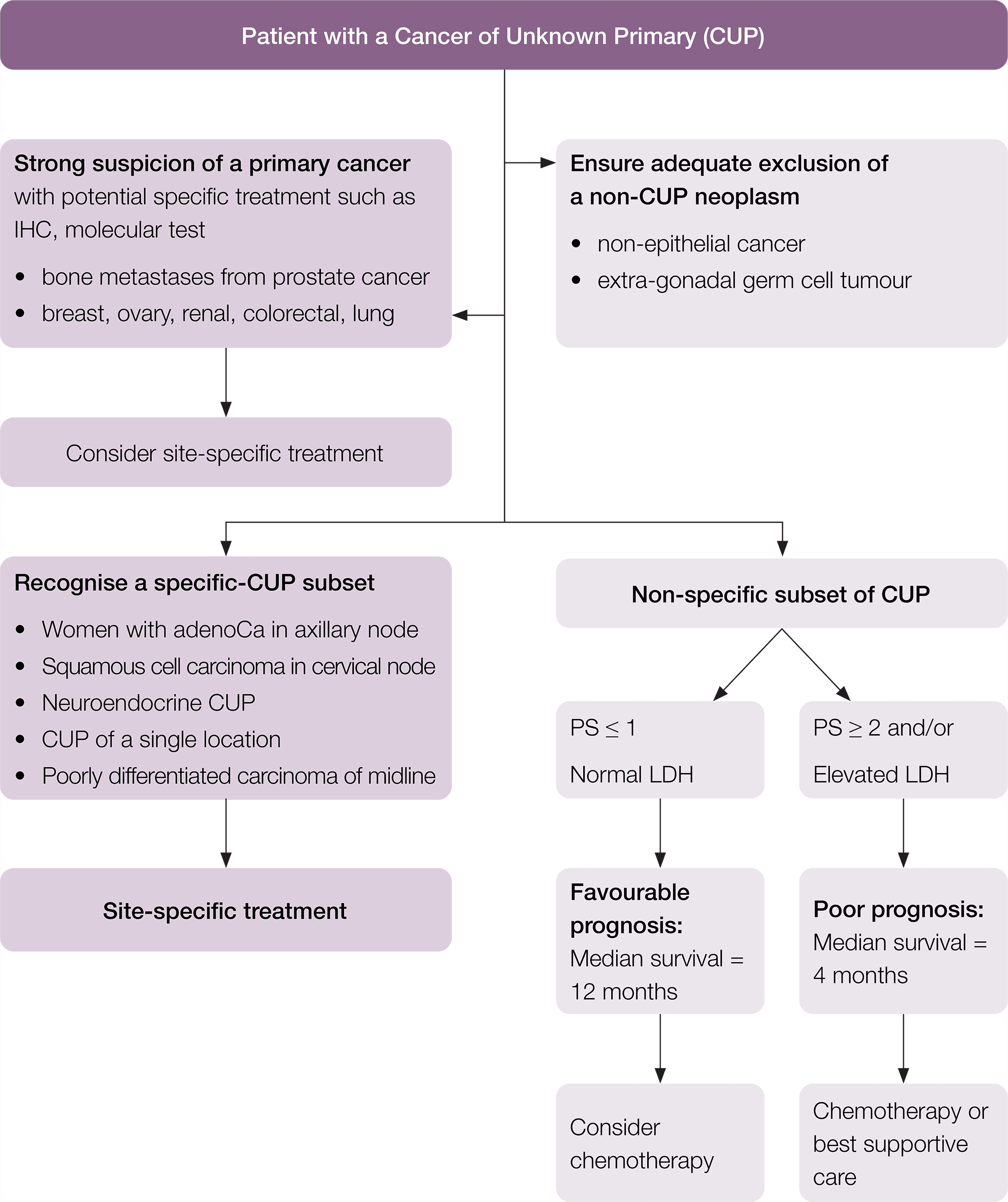

Treatment should be individualised according to the clinico-pathological subset and the suspected primary site. The following treatment recommendations have been adapted from the ESMO guidelines (Fizazi et al. 2015).

A suggested flow chart to guide treatment is provided.

* Fizazi K, et al. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up, Annals of Oncology 2015; 26 (suppl_5): v133–v138 doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv305. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of ESMO. Oxford University Press and ESMO are not responsible or in any way liable for the accuracy of the adaptation, for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefore. Cancer Institute NSW is solely responsible for the adapted material in this work. Please visit the ESMO Cancers of Unknown Primary Site website.

Patients in the specific-CUP subset who have a good prognosis should be treated the same as patients with equivalent known primary tumours with metastatic disease, as shown in Table 1.

|

Equivalent known primary tumour |

Recommended treatment |

|

Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary |

Treat as poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas with a known primary |

|

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour of unknown primary |

Treat as well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour of a known primary site |

|

Peritoneal adenocarcinomatosis of a serous papillary histological type in females |

Treat as ovarian cancer |

|

Isolated axillary nodal adenocarcinoma metastases in females |

Treat as breast cancer |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma involving non-supraclavicular cervical lymph nodes |

Treat as head and neck squamous cell cancer |

|

CUP with an intestinal phenotype and IHC (CK20+/CDX2+/CK7−) or molecular profile |

Treat as metastatic colorectal cancer |

|

Single metastatic deposit from unknown primary |

Treat as single metastases by resection or high-dose (ablative) radiotherapy depending on the location |

|

Osteoblastic bone metastases or IHC/serum PSA expression in men |

Treat as prostate cancer |

|

Patients with extragonadal germ cell syndrome |

Treat as poor-prognosis germ cell tumour (Greco 2013). |

|

Isolated inguinal adenopathy (squamous carcinoma) |

Local dissection with or without local radiotherapy (Pavlidis et al. 2015) |

Other tumour specific optimal care pathways can be found here.

* Fizazi K, et al. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up, Annals of Oncology 2015; 26 (suppl_5): v133–v138 doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv305. Adapted and reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of ESMO. Oxford University Press and ESMO are not responsible or in any way liable for the accuracy of the adaptation, for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefore. Cancer Institute NSW is solely responsible for the adapted material in this work. Please visit the ESMO Cancers of Unknown Primary Site website.

For patients with a non-specific subset of CUP, but who have a favourable prognosis, a two-drug chemotherapy regimen as per the NCCN or ESMO guidelines should be considered (Culine et al. 2003, Gross-Goupil et al. 2012, Hainsworth et al. 2010).

Patients with localised disease may be suitable for local therapies such as high-dose (ablative) radiotherapy (Janssen et al. 2014) or surgical excision.

CUP patients identified in the poor-prognosis non-specific group can be considered for treatment with low-toxicity, palliative, chemotherapy regimens and/or best supportive care (Fizazi et al. 2015).

Using palliative radiotherapy to relieve local symptoms should also be considered where appropriate (Rich & Mendenhall 2016, Tey et al. 2017). In addition, other palliative procedures to assist in symptom control may also be considered in specific situations such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery pleurodesis or PleurX (if available) for interventional pain relief.

Timeframe for commencing treatment

Timeframes for diagnosis should be informed by evidence-based guidelines (where they exist) while recognising that shorter timelines for appropriate consultations and treatment can reduce patient distress.

Treatment of CUP should begin within two weeks of the decision to treat (four weeks from referral).

Participation in research and/or clinical trials should be encouraged where available and appropriate.

- Australian Cancer Trials is a national clinical trials database. It provides information on the latest clinical trials in cancer care, including trials that are recruiting new participants. For more information visit the Australian Cancer Trials website.

The following training and experience is required of the appropriate specialist(s):

- Medical oncologists (RACP or equivalent) must have adequate training and experience with institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004).

- Nurses must have adequate training in chemotherapy administration and handling and disposal of cytotoxic waste.

- Chemotherapy should be prepared by a pharmacist with adequate training in chemotherapy medication, including dosing calculations according to protocols, formulations and/or preparation.

- In a setting where no medical oncologist is locally available, some components of less complex therapies may be delivered by a medical practitioner and/or nurse with training and experience with credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area under the guidance of a medical oncologist. This should be in accordance with a detailed treatment plan or agreed protocol, and with communication as agreed with the medical oncologist or as clinically required.

- Radiation oncologist (FRANZCR or equivalent) with adequate training and experience that enables institutional credentialling and agreed scope of practice within this area (ACSQHC 2004) and who is also a core member of an oncology MDT.

These include:

- a clearly defined path to emergency care and advice after hours

- access to basic haematology and biochemistry testing

- cytotoxic drugs prepared in a pharmacy with appropriate facilities

- occupational health and safety guidelines regarding handling of cytotoxic drugs, including safe prescribing, preparation, dispensing, supplying, administering, storing, manufacturing, compounding and monitoring the effects of medicines (ACSQHC 2011)

- guidelines and protocols to deliver treatment safely (including dealing with extravasation of drugs)

- appropriate nursing and theatre resources to manage complex surgery

- 24-hour medical staff availability

- 24-hour operating room access

- specialist pathology

- in-house access to radiology

- an intensive care unit

- trained radiotherapy nurses, physicists and therapists

- access to CT/MRI scanning for simulation and planning

- mechanisms for coordinating combined therapy (chemotherapy and radiation therapy), especially where the facility is not collocated

- access to allied health, especially nutrition health and advice.

Unless favourable and treatable disease is defined, CUP represents a group of patients who have a very poor prognosis. It has been demonstrated that CUP patients receive less treatment and have poorer survival compared with those with cancer of known primary sites (Riihimaki et al.2013a, Schaffer et al. 2015). Many people with CUP may benefit from palliative treatments to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life and manage the uncertainty of their prognosis more effectively.

Palliative care interventions should be considered for all patients diagnosed with CUP (NCCN 2017). It is preferable for specialist palliative care to be initiated during the diagnostic stage, and for many patients this will remain the most important intervention during their illness (Abdallah et al. 2014).

Early referral to palliative care can improve the quality of life for people with cancer including improving the capacity of patients to sit comfortably with diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty and better management of physical and psychological symptoms (Haines 2011, Temel et al. 2010, Temel et al. 2017, Zimmermann et al. 2014). This is particularly true for poor-prognosis cancers (Cancer Council Australia 2017, Philip et al. 2013, Temel et al. 2010, Temel et al. 2017). Furthermore, palliative care has been associated with improved wellbeing for carers (Higginson & Evans 2010, Hudson et al. 2014).

Ensure carers and families receive information, support and guidance regarding their role according to their needs and wishes (Palliative Care Australia 2005).

The patient and carer should be encouraged to develop an advance care plan (AHMAC 2011).

Further information

Refer patients and carers to Palliative Care Australia.

The lead clinician should discuss the patient’s use (or intended use) of complementary or alternative therapies not prescribed by the MDT to identify any potential toxicity or drug interactions.

The lead clinician should request a comprehensive list of all complementary and alternative medicines being taken and explore the patient’s reason for using these therapies and the evidence base.

Many alternative therapies and some complementary therapies have not been assessed for efficacy or safety. Some have been studied and found to be harmful or ineffective.

Some complementary therapies may assist in some cases, and the treating team should be open to discussing the potential benefits for the patient.

If the patient expresses an interest in using complementary therapies, the lead clinician should consider referring them to health professionals within the MDT who have knowledge of complementary and alternative therapies (such as a clinical pharmacist, dietitian or psychologist) to help them reach an informed decision.

The lead clinician should assure patients who use complementary or alternative therapies that they can still access MDT reviews (NBCC & NCCI 2003) and encourage full disclosure about therapies being used (Cancer Australia 2010).

Further information

- See Cancer Australia’s position statement on complementary and alternative therapies.

- See the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia’s position statement.

Screening with a validated screening tool (such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer and Problem Checklist), assessment and referral to appropriate health professionals and/or organisations is required to meet the needs of individual patients, their families and carers.

In addition to the common issues outlined in the Appendix, specific needs that may arise at this time include the following.

Physical needs

- Fatigue/change in functional abilities is a common symptom, and patients may benefit from a referral to occupational therapy.

- Decline in mobility and/or functional status may result from treatment.

- Assistance with managing complex medication regimens, multiple medications, assessment of side effects and assistance with difficulties swallowing medications may be required. Refer to a pharmacist if necessary.

Psychological needs

- Patients may need support with emotional and psychological issues including, but not limited to, body image concerns, fatigue, existential anxiety, treatment phobias, anxiety/depression, interpersonal problems and sexuality concerns.

- Many patients with CUP find the uncertainty surrounding their disease and the limited treatment options difficult and would welcome the opportunity to ask questions and learn about others’ experiences (Boyland & Davis 2008).

- Many patients with CUP and their clinicians have a poor understanding of their illness, have difficulty in explaining their illness to others, and develop a sense of frustration in health professionals not having the answers (Boyland & Davis 2008, Karapetis et al. 2017).

- Depressive symptoms are higher in people with CUP when compared with people with cancer of a known origin, so they require more psychosocial support and specific interventions (Hyphantis et al. 2013).

- Palliative care can improve physical symptom control and the quality of life for people with cancer including improving the capacity of patients to come to terms with diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty (Temel et al. 2017).

- GPs play an important role in coordinating care for patients, including assisting with side effects and offering support when questions or worries arise. For most patients, simultaneous care provided by their GP is very important (Lang et al. 2017).

Social/practical needs

- Patients may need support to attend appointments.

- Potential isolation from normal support networks, particularly for rural patients who are staying away from home for treatment and for patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms, can be an issue. Social isolation can also compound distress (Australian Cancer Network 2009).

- Financial issues related to loss of income and additional expenses as a result of illness and/or treatment may require support.

- Help with legal issues may be required including advance care planning, appointing a power of attorney and completing a will.

Spiritual needs

- Multidisciplinary teams should have access to suitably qualified, authorised and appointed spiritual caregivers who can act as a resource for patients, carers and staff.

- Patients with cancer and their families should have access to spiritual support appropriate to their needs throughout the cancer journey.

Information needs

- CUP patients are more likely to want written information about their type of cancer and tests received but are less likely to understand explanations of their condition (Wagland et al. 2017).

- Provide appropriate information to patients and carers about how to manage alterations in cognitive function and potential changes in behaviour.

- Patients may need advice about safe driving.

- Patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds may need information provided in other formats.

The lead clinician should:

- discuss the treatment plan with the patient and carer, including the intent of treatment and expected outcomes (provide a written plan after final histopathological diagnosis (not frozen section) is available)

- provide the patient and carer with information on possible side effects of treatment, self- management strategies and emergency contacts

- initiate a discussion regarding advance care planning with the patient and carer.

The lead clinician should:

- communicate with the person’s GP about their role in symptom management, psychosocial care and referral to local services

- ensure regular and timely two-way communication with the GP regarding:

- the treatment plan, including intent and potential side effects

- supportive and palliative care requirements

- the patient’s prognosis and their understanding of this

- enrolment in research and/or clinical trials

- changes in treatment or medications

- recommendations from the MDT.